satori.lv

No 1 “I want to film life itself, not one that is acted out.”

Hertz said he was born a sad, albeit lucky man. Indeed, the life of Frank’s Jewish family was a series of dramas. His mother died when he was fifteen, during the Second World War two of his sisters perished in a concentration camp, one brother was severely wounded, and his third sister spent ten years in the Gulag. In comparison to them, he could be considered lucky, but who’s to say whether a witness to such events suffers any less.

From an early age, Hertz was surrounded by the harsh realities of life, but despite all odds he retained an awe for reality; he was like this from a very young age and began to “think in frames”—to notice inconsistencies, to pick out “traces of the soul” even in the soulless. It seems he had many questions about life from early on, the answers to which he tried to find in his immediate surroundings. “To uncover the essence of something means to some (or perhaps a great) extent to come to a solution” he would say many years later. The desire to “uncover the essence” would become the primary aim of his work.

diena.lv

Hertz spent most of his childhood in Ludza, a small town in eastern Latvia. It was here that the pops of the camera flash of his father, a professional photographer, lit a spark of creativity in his soul. Theatre, photography, cinema—this was what made up Frank Sr. His son took one of these and made it his life’s mission.

No 2 “Knowledge is power and ignorance is the driving force.”

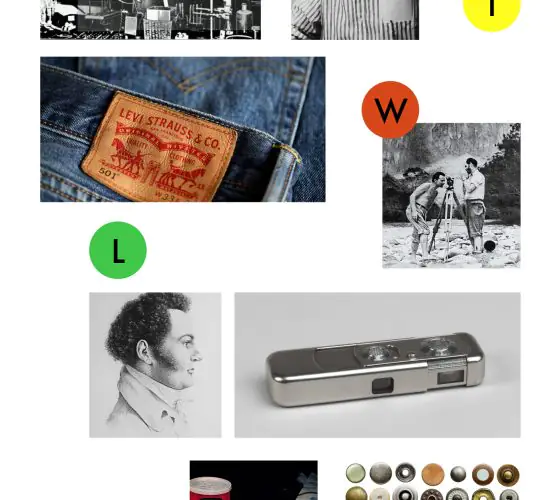

Hertz was already in his 30s when he at last came to his cherished craft as a professional, no longer an amateur. However, before that he had managed to serve in the army, finish law school and work as a journalist. He then landed a job as a photographer at the Riga Film Studio, which opened the door to cinema for him. Not long after that, he managed to establish himself as a screenwriter (his journalistic experience came in handy). Later he would often say that due to his lack of professional education in the field, he didn’t know how to do it properly in the beginning—in scriptwriting, in the director’s chair; that he often acted somehow by feel. Perhaps that’s what made him such an innovator in the end.

Hertz was constantly experimenting. He had the habit of taking unrelated photos and trying to find something in common between them. Then, right there on his desktop, he laid them out so that they formed a complete narative, or, as he liked to call it—”life”. He later applied this to his films.

His most important work at the time was the script for the film “The White Bells”, which later made its way into Latvia’s Cultural Cannon as one of the twelve most outstanding works in the history of Latvian cinema.

No 3 “We have abandoned slogans in our films and turned to the human soul.”

The motto of the Riga School of Poetic Documentary Cinema, of which Hertz was one of the founders. The idea came there, at the Riga Film Studio, partly due to the excess of overly politicised cinema. The first film by the school’s members—the very same “White Bells”—was a hit. A little girl in a white dress walks through the streets of Riga in the early 60s, and suddenly in the window of a flower shop she notices fresh white bells. But the shop is closed. Now she has to find white bells by any means necessary.

filmas.lv

This film is a wonderful chronicle of what happened sixty years ago on the streets of the Latvian capital, but even more important is its poetry, which can only be fully understood by watching the film in its entirety. The story is inspired by a real memory of Hertz’s:

“One evening, as I was crossing the street, I noticed a carnation on the pavement—it appeared as though someone had dropped it. It could have survived under the wheels by chance alone, so it seemed to me. But when I came closer, among the many traces of tyremarks, I clearly saw that one of them had sharply avoided the carnation. It was not difficult to imagine how the car was rushing with its right wheel directly in front of the flower and how at the last second, in the final metre, the driver, noticing it, swerved sharply. I could almost hear the “scream” of the brakes and thought to myself: here was a soulless car leaving a trace of a human soul on the asphalt…”

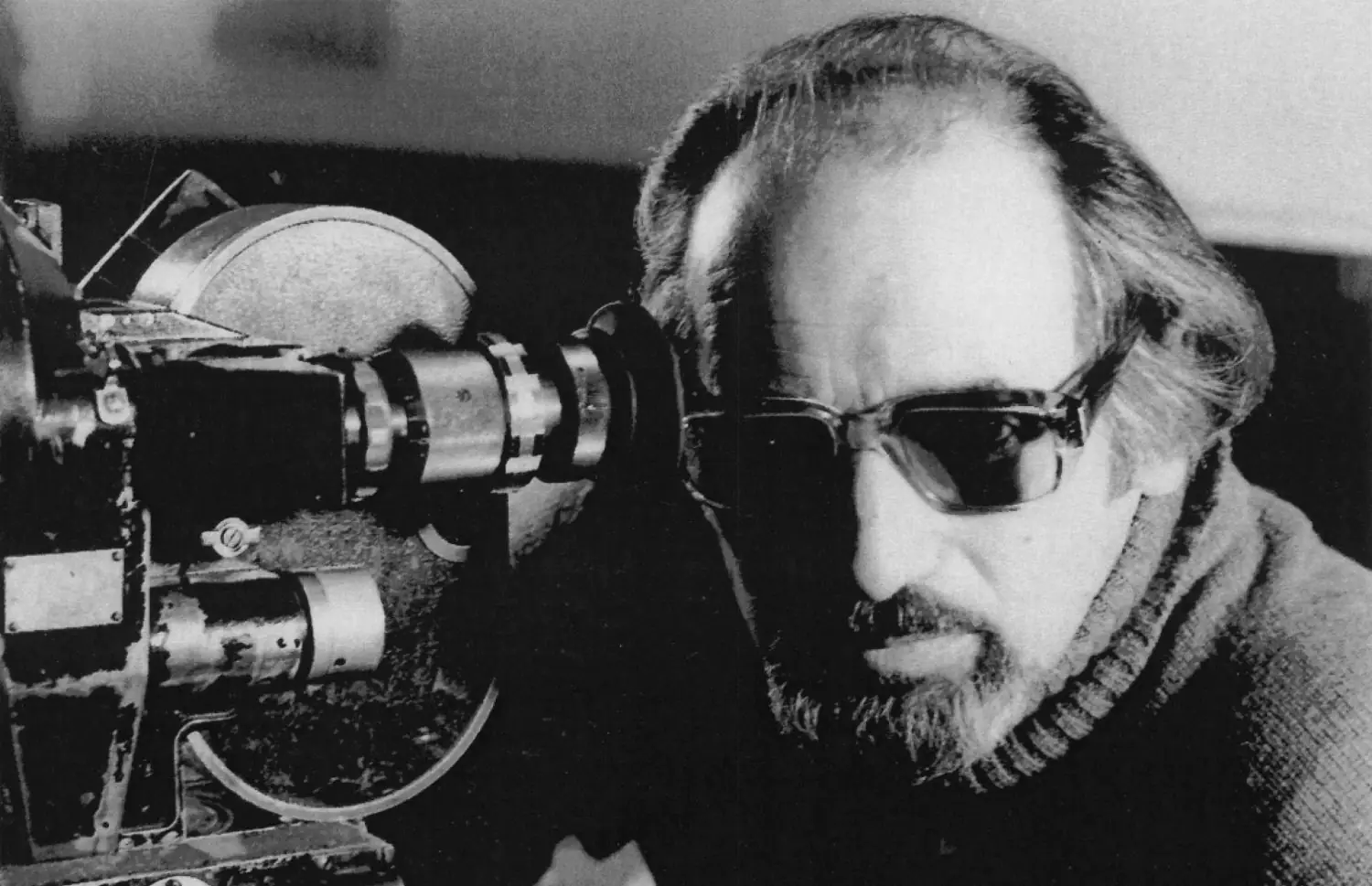

From the moment of childbirth in “The Song of Songs” to the confession of a criminal sentenced to execution in “The Last Judgement” to the surgery on his own heart, Hertz often, indeed almost always, touched upon poignant, at times shockingly blunt, subjects. But right from the beginning of his career, he set out to understand the human soul, and without a certain sharpness that was simply impossible.

No 4 “All my life I have filmed other people’s lives and all the time I question whether I have the right to expose them.”

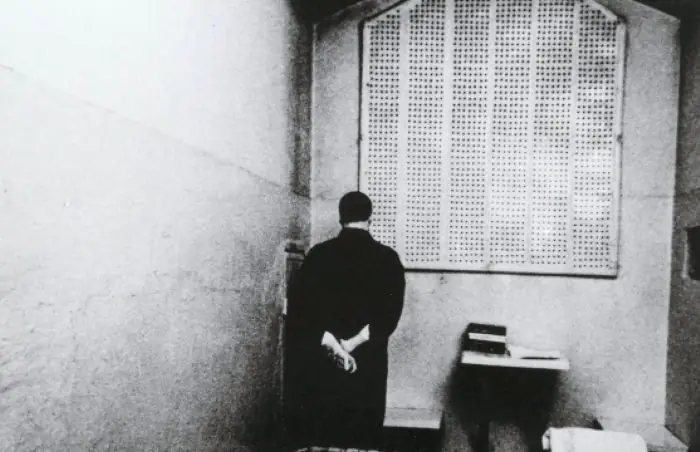

Hertz captured as often as possible the moments of clash between the opposites of mankind—good and evil, joy and fear. That’s why he chose to film people in tough situations: a convict in prison, a woman in hospital during labour.

filmas.lv

He did not shy away from stories ladened with contradictions.

But even when he captured his conversation with a convicted criminal in “The Last Judgement” he was not filming a criminal, but rather a human being. The only thing he wished to achieve with this kind of film was to understand, or at least try to understand, the human soul. Whatever story he was shooting, he always followed his moral code: to never use the camera to harm another. He seemed to be very good at it, but not only because of his morality: his boundless love for others played a crucial role.

No 5 “We shot neither theatre, nor fairy tales about good and evil; we plunged straight into the mysteries of the human soul.”

The film “Ten Minutes Older” is one of the earliest and most exemplary illustrations of Hertz’s directorial work. A short, ten-minute film without a single cut, and the director’s second work to enter Latvia’s Cultural Canon. There seems to be more to the film than the simple plot suggests: a little boy watches a puppet show. The viewer does not hear a single word, only music. Hertz managed to shoot the film in such a way that for those ten minutes, the boy’s eyes turn into mirrors, reflecting the viewer’s soul as they react to the events unfolding on screen. “It’s a whole slice of life, a soulful life, seen in its flow and shot report-style, in one continuous shot,” Hertz said of his own work.

chayka.lv

“Ten Minutes Older” continues to inspire filmmakers around the world. One of the most famous examples is Wim Wenders’ “Ten Minutes Older: The Trumpet” (2002). His work also touches on the boundlessness of the soul.

Hertz Frank is the child who wanted to comprehend the world around him and came to the conclusion that the only place to start was the incomprehensible human soul.

Before his death in 2013, the director had managed to amass admirers from all over the globe—mainly Latvia, Russia, Germany and Israel, where he spent the last twenty years of his life.

A selection of Frank’s films is available at filmas.lv.