Riga’s bakery with the German—sounding name Glückauf seems to be deliberately hiding from intrusive guests in one of the small streets of what’s known as the Quiet Centre. However, on Thursday and Friday—the days when Glückauf is open to the public—regular and newly curious customers alike regularly stop by.

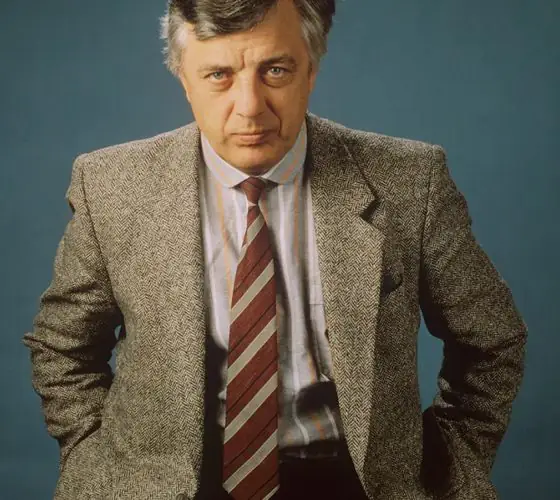

The Glückauf bakery opened a few years ago, at the height of the pandemic. Its creator, Elena Zakharenko, bakes bread herself, takes orders, communicates with visitors, tries and develops new recipes.

About the childhood, a bread masterclass in a monastery and the name of the bakery

Glückauf is how German miners greet each other, right? That’s what it says on your website.

Yes, it’s been a familiar word to me since I was a child. I was born in Germany, spent several years there. My dad, a simultaneous interpreter, worked at a uranium ore mining company. So “Glückauf!”—a greeting, a farewell and a wish of good luck—was very natural to me.

It immediately came to mind when my husband and I were thinking of a name for our bakery. I wanted it to include a positive message, as well as a deeper meaning. Today, almost all coal mines in Germany are closed. It’s a story of a large number of families, their tragedies and joys. That is why such a name was chosen in memory of this gruelling profession, the families connected with it and a little bit of my childhood in Germany.

Is your love for and such a careful attitude towards bread also from your childhood?

Yes and no. My interest in bread came much later. Although, I likely subconsciously absorbed the bread culture I experienced in Germany.

For example, German buns! It was the first thing on the table for breakfast. Or another tradition: wake up early and go for fresh bread, buy exactly as much as you need, no more and no less, because tomorrow you have to repeat this ritual again. It is the quintessential German way of doing things.

You mentioned that your interest in bread came much later.

That’s true, however, now, as I look back on it, I realise that it was meant to be this way. There are two curious stories that seem to confirm this.

My mother once told me that when I was born there was a small bakery opposite our house in Germany. The owners lived on the first floor of the building and they baked bread on the ground floor. Mum used to go there all the time to get freshly baked goods. I don’t remember that, of course, but that has been cemented in my memory. Now I tell this story to my children. I once even took them to see the place.

Here is another story. When my parents’ work in Germany came to an end, we started packing for Moscow. There was a terrible shortage then, so we tried to buy everything we could in Germany. And for some reason my mum bought me a spatula for baking. A little red one. She handed it to me with the words: “Maybe you’ll bake a cake one day.” I don’t think I ever baked a cake, but I kept the little red spatula.

So your mother encouraged you to bake?

To say that would probably be a bit misleading. All of my life experience has led me to the business I’m in now.

I really never baked as a child. We didn’t even have an oven in our house. Bread came into my life almost by accident—only seven years ago.

I had a very bad case of sore throat, and it took me a long time to recover. My doctor put me on a strict diet and the only thing I was allowed to eat were cucumbers. That’s when I came across a page about sourdough bread—healthy and tasty. I immediately imagined my grandmother in the countryside, in the process of diligently souring food… and I became curious.

The first “bread masterclass” I ever attended took place on the site of a men’s monastery in the Moscow region. I remember that early in the morning on the day of the masterclass, a large bread delivery van came to pick me up. In the evening I returned in the same van, but with a baking stone and moulds. I was alone at that masterclass, writing something down, not really fully aware of what was going on, just watching. Yet I still remember the smell of that monastery bread: we greased the baking mould not with oil, but with beeswax, so when the bread was delivered from the oven, the aroma was indescribable.

And then…once you attend one masterclass, it’s hard to stop.

I couldn’t believe it for a long time—that it was possible to find “my” business just like that. But when customers come to me with kind words, it means so much—that everything was not in vain.

On speciality bread, sourdough and the secret of brioche

Glückauf bakes bread and rolls exclusively from sourdough. The long and careful preparation process gives the bread its delicate flavour, generous aroma, crispy crust, as well as its unique benefits and quality.

All recipes are the result of courses Elena took in Spain, France and Germany, as well as long hours spent in the kitchen honing her skills and perfecting recipes.

Tell us about the bread you bake at Glückauf. What kind of bread do customers buy the most?

At Glückauf, we bake according to German and French recipes. The first bread we had was a French rustic type, la tartine. With a spongy inside and a bronze crust. And our speciality, charcoal bread. Then the menu expanded with French baguettes and brioche.

In the beginning we had another bread—wurzel. Very tasty, made of three kinds of flour, as if twisted into a plait. Why it didn’t work in Riga is still a mystery to me. There is a curious pattern: if a classic baguette and a wurzel are lying next to each other, people will choose the baguette. We’ve done everything we can: we’ve organised tastings, we’ve told people. But no, the baguette always wins.

Another one of our popular breads is buckwheat bread. It’s definitely a favourite with those who aren’t fond of regular breads.

Finally, we make petit fours, which is the name given to a variety of small pastries. For example, bretzels, stollen, sandwiches, brioche buns with different fillings, and we recently launched a black pizza with artichoke and tuna. At first, of course, we took it slowly, having learnt from Wurtzel. But it took off.

I’ll share a curious fact: when we first opened, Edgars Rinkevics, then Latvia’s foreign minister, used to come in every day. He invariably chose black coffee and a brioche bun with brie cheese and thyme.

And all this, of course, on sourdough. What is the secret of its popularity and why do many people now specifically seek it out?

Ordinary bread—which, for example, you can buy in the supermarket—is made with industrial yeast. It only takes an hour to rise, but sourdough bread takes a few days.

Because of the long process of curing, it has much more lactic acid bacteria. This makes the bread healthier, better quality and tastier. And it doesn’t come with the sensation of a heavy stomach as with typical bread.

By the way, German bakers very rarely mix yeast and sourdough. The French, on the contrary, add a dash of yeast to almost all sourdough starter.

It’s probably pointless to ask which bread on the Glückauf menu is your favourite?

It’s true, I don’t have a favourite. It’s like choosing which child is your favourite. I love absolutely everything we sell.

I do have one secret, though.

I think brioche is the best thing that can happen to you when your mood is low and everything seems to be slipping from your hands. Take a still warm brioche, don’t cut it, just break off a piece and eat it. And if you also have coffee with the brioche, there’s no chance.

On balance and bread meditation

You opened during the pandemic—to put it lightly, not the most favourable period for business. Was it daunting?

To be honest, not really. I remember the first customers came in wearing masks and foggy glasses. And I was absolutely absorbed in the process: my day consisted of constantly looking for new bakers, training them, supervising them—in a never—ending cycle.

At the time, I guessed that something was wrong, but what was it? The bakery worked, the first regular customers appeared—without advertising, just word of mouth. But I felt that it didn’t bring me any pleasure. And then life put everything in place.

I realised that I could only give people joy if I felt positive emotions myself.

How does one achieve that? Change the way you approach your business.

What did you change?

We used to be open for customers five days a week, now only on Thursdays and Fridays. This is the volume that I can steadily and happily do myself with the help of an assistant. We bake bread that customers order in advance, and we also make a few more of each type. I believe it’s better if on some days someone doesn’t get bread rather than having extra left over.

This approach has also allowed me to work with restaurants. For example, you can find our brioche at Lowine, charcoal rolls at Space Falafel, and French rustic at Kase.

So I gave up the exhausting process of constantly searching. That turned out not to be the point, rather I had to listen to myself. It’s not easy to do that, but how much change that brings afterwards is worth it.

It seems you’ve managed to achieve a healthy balance. We saw your post about a masterclass, which is about the same thing—finding balance.

Yes, we have held master classes before, but since March we have launched a new programme called “Bread Therapy”.

When I was out of the kitchen and working at the cash register, I got the chance to interact with customers a lot (sometimes I get the feeling that I not only have a bakery, but an information bureau and a dating club all in one).

We live in difficult times—I see that many people are hanging in there, but at some point life can get very hard and overwhelming. I realised that it wasn’t exactly me who could help cope with it, but actually bread. Like it once helped me.

At “Bread Therapy” participants knead their own bread. It’s a meditative process. We organise small, comfortable groups of just six people. So we rely on the healing power of people and bread.

In the end, it certainly seems to work.