lsm.lv

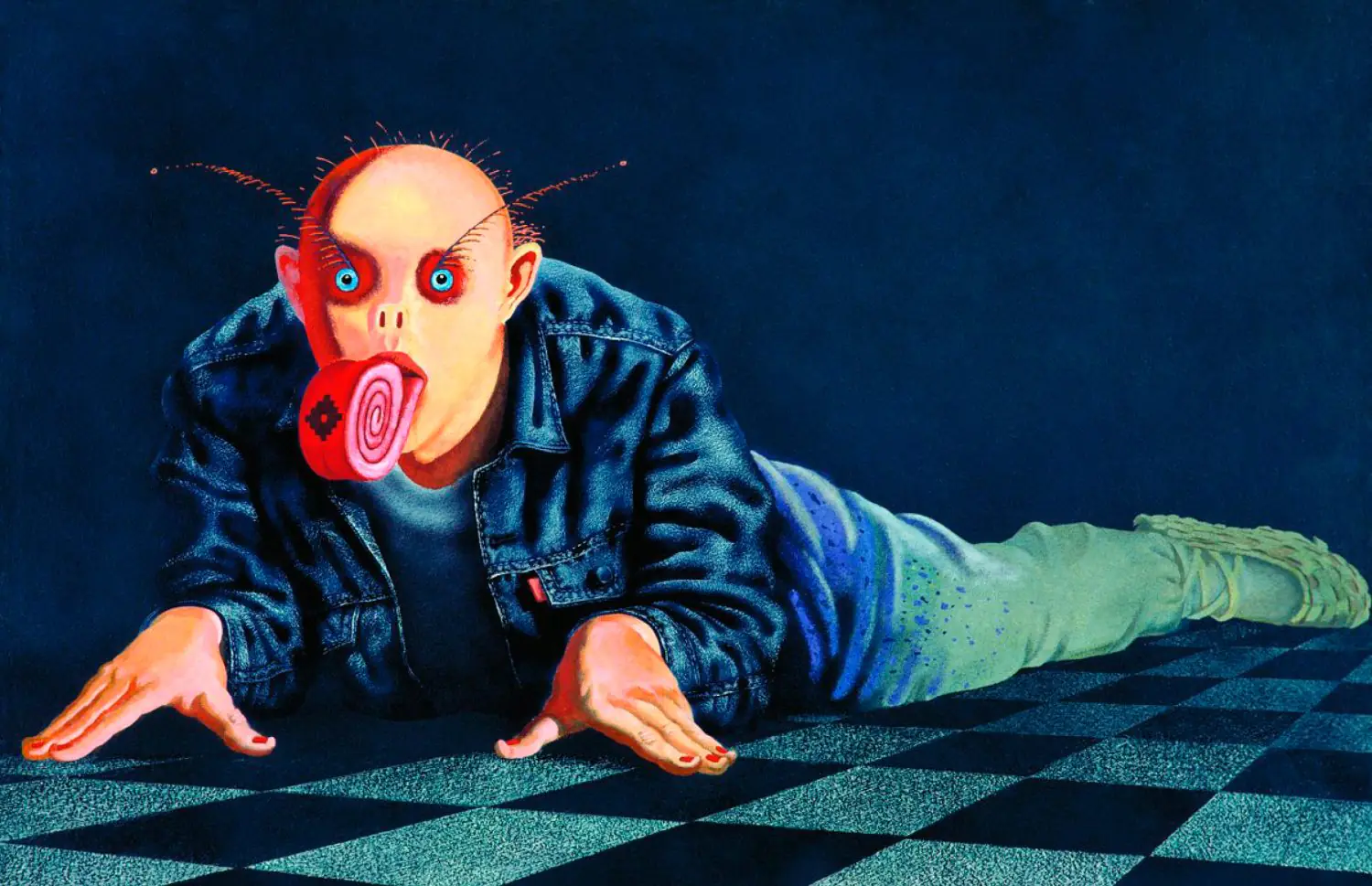

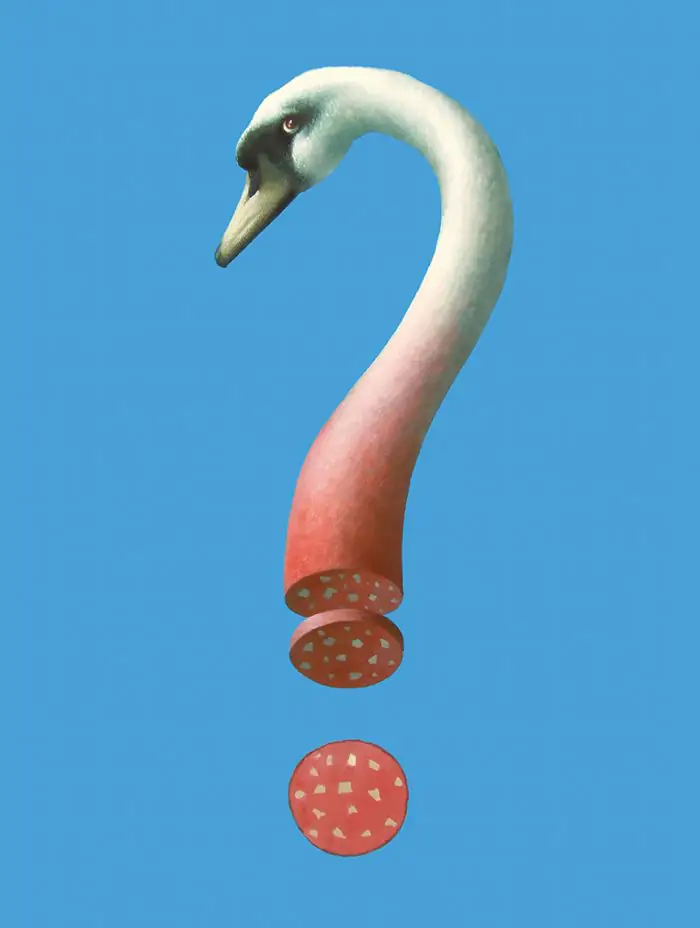

In 2018, the Lielais Dzintars concert hall in Liepāja hosted an exhibition titled “POSTERTIME / The Canon and Individuality” curated by art historian Ramona Umblia. Among the 32 exhibits, one of the headline works was the image of a man with a coiled tongue and sprawling eyebrows like the antennae of an insect. The man is lying on a chequerboard floor, and is looking directly at the viewer. His fingernails are painted, his head is shaved, and he wears traditional Latvian bast shoes.

This grotesque, eerie piece is the famous “Chameleon” poster. The surrealism with which the artist Juris Putrams endowed it is part of a great tradition of poster painting in Latvia. “Chameleon” came about in the 1980s, when poster art was most active in the Baltic republics of the USSR, and a whole array of talented poster artists worked in Latvia.

The first posters and political censorship

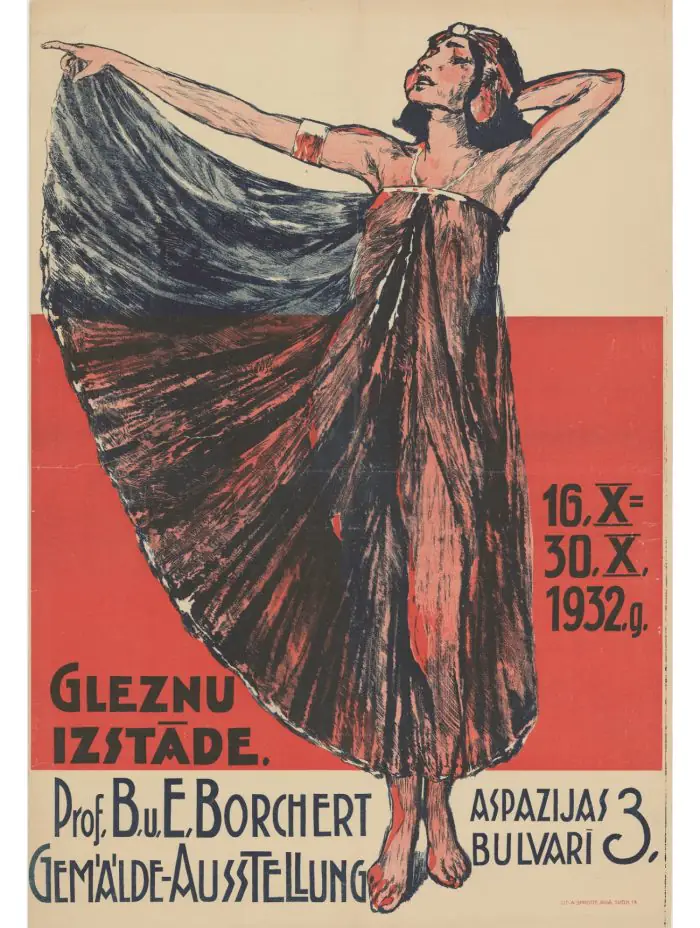

The first posters in Riga began being printed in the late 19th and early 20th century. They were created by many famous artists—the title and specialisation “poster artist” was established much later. Among those who created posters for art exhibitions (including their own) and other events were Rihards Zariņš, Bernhard Borchert and Jānis Rozentals.

journals.openedition.org

journals.openedition.org

Poster art in Latvia developed rapidly during the Soviet occupation. This was a direct reaction to the censorship of the USSR: from the 1930s, the defining artistic style in the Union was the so-called Socialist Realism, a trend that was officially named in 1934. Its main consumer, customer and addressee were the nomenklatura.

Artists and creatives were required to ”depict exactly what the state wanted to see”, writes art historian Galina Elshevskaya: hyperbolised industrial landscapes, the triumphant abundance of the socialist system and portraits of the leaders. Criticism of the state and any departure from the official canon was not only unwelcome, but could lead to a ban on the profession and further repression.

After Stalin’s death, the situation in the creative environment improved somewhat: artists were given relative freedom and the opportunity to return to abstract art, which was developing actively at the time. But it didn’t last long: at a 1962 Moscow art exhibition in the Manege, General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev decried modern art and called abstractionism “smear”. Soon after, easel painting came back under close scrutiny, and abstract art disappeared from the agenda.

Artists who did not agree with the party’s policy were left with two options: to further their artistic vision behind closed doors or to seek other means of self-expression. It was largely for this reason that talented people of the time pursued furniture design, architecture, arts and crafts or graphic design. How this worked in the case of the poster, curator Ramona Umblia explains:

“The “Soviet Standard” was socialist realism, naturalistic drawing, and super-human—that is, a Soviet man fighting for a better future. Here—a complete and utter departure from ideology. There—talking directly to the person, and the main thing is that the poster is art, not an ideological weapon.”

In Soviet times, among some artists, the term “poster” was rather pejorative because of its association with art that glorified the Soviet regime. However, in Latvia, as well as in the Baltic States in general, the poster turned from an ideological mouthpiece into an independent genre of graphic design, and in some cases became an instrument of resistance.

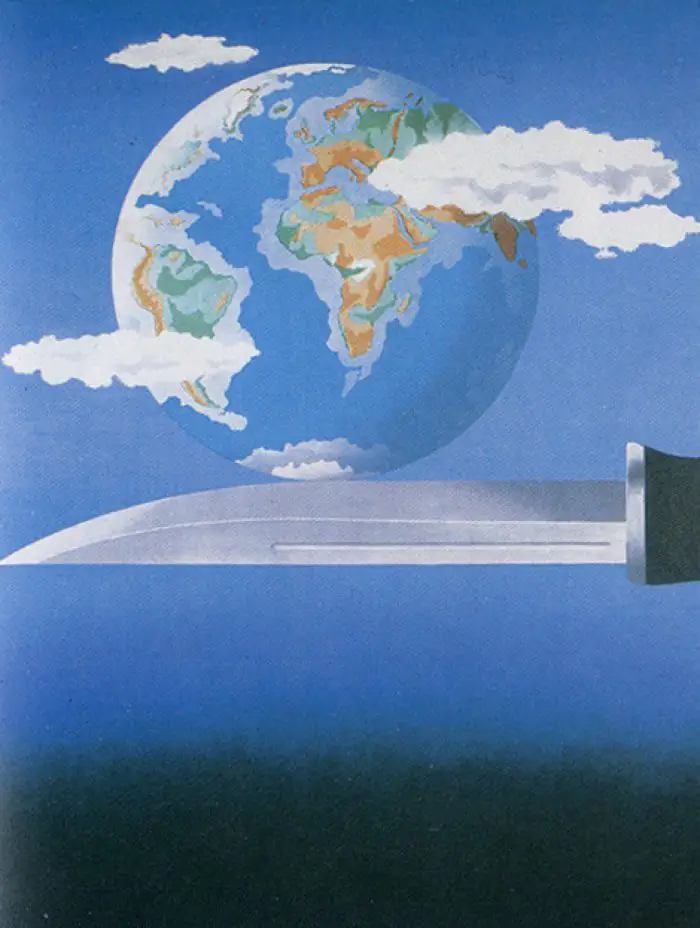

For example, when the authorities forbade the use of national flags of the independence period in their images, poster artists depicted the symbols in more cryptic ways. This was a kind of cipher—a carefully coded form of counter-propaganda and a way of preserving national independence through art.

kulturaskanons.lv

As researcher Marc Gaber writes in this article, the originality of poster art in Latvia was largely determined by the fact that local artists maintained close ties with other European countries outside the official USSR, especially Poland. They sent their posters to international competitions and in some cases won prizes: for example, in the 1970s, Laimonis Šēnbergs’ work “For the progress of human thought” won a prize at the Warsaw Biennale.

The History of the Latvian Poster

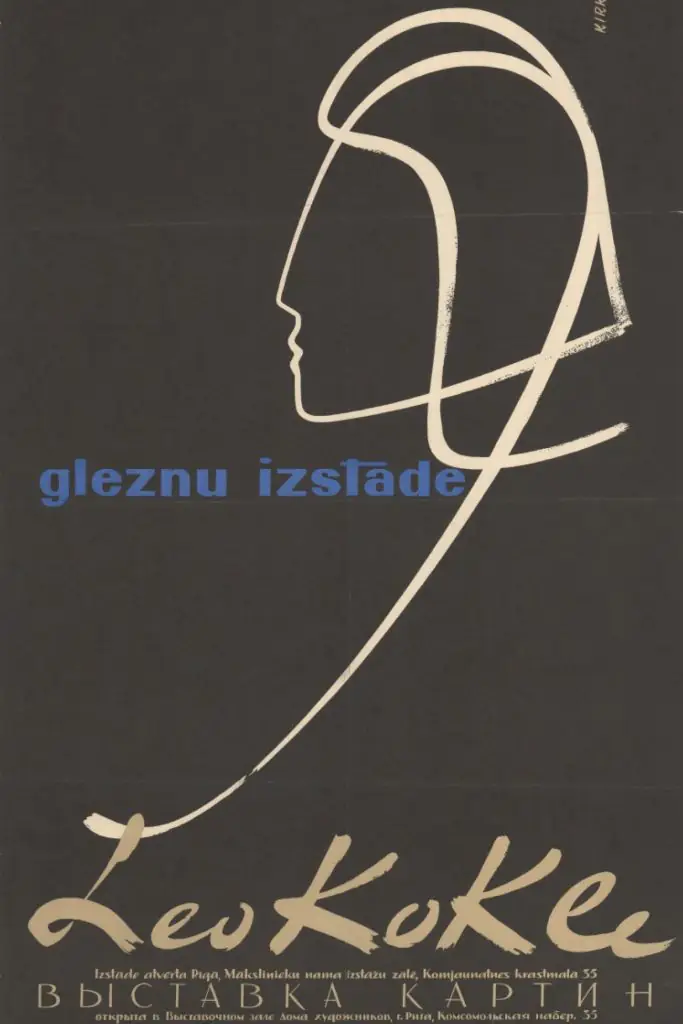

The work of Gunārs Kirke is considered a turning point in the history of Latvian poster art. In 1963, he created a poster for the exhibition of landscape painter Leo Kokle, thus laying the foundations of modern poster art. From that moment on, the poster movement in Latvia developed so rapidly that the first Latvian poster exhibition took place just three years later. Along with works commissioned by state bodies, posters containing unbiased and subjective artistic statements were exhibited there for the first time.

Gradually a circle of outstanding artists formed around Kirke, who devoted themselves to the art of the poster: for example, the painter Juris Dimiters, stage designer Ilmārs Blumbergs, designers Laimonis Šēnbergs and Gunārs Lūsis, Georgs Smelters and others.

It is noteworthy that not all of them had specialised education—Smelters was one of the few who had graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts’ graphic arts department. However, in this case it was rather a boon and helped the trend to develop into a cultural phenomenon. The diverse specialisations of poster artists helped each of them to form a unique creative approach, which was influenced not by university dogmas, but by the specifics of their professional environment and personal experiences.

kulturaskanons.lv

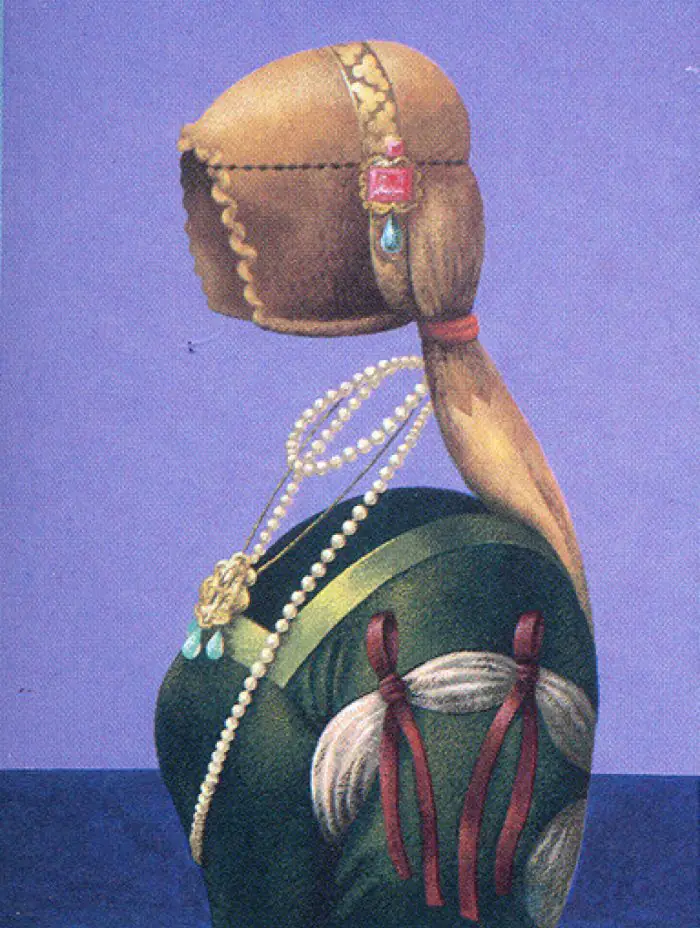

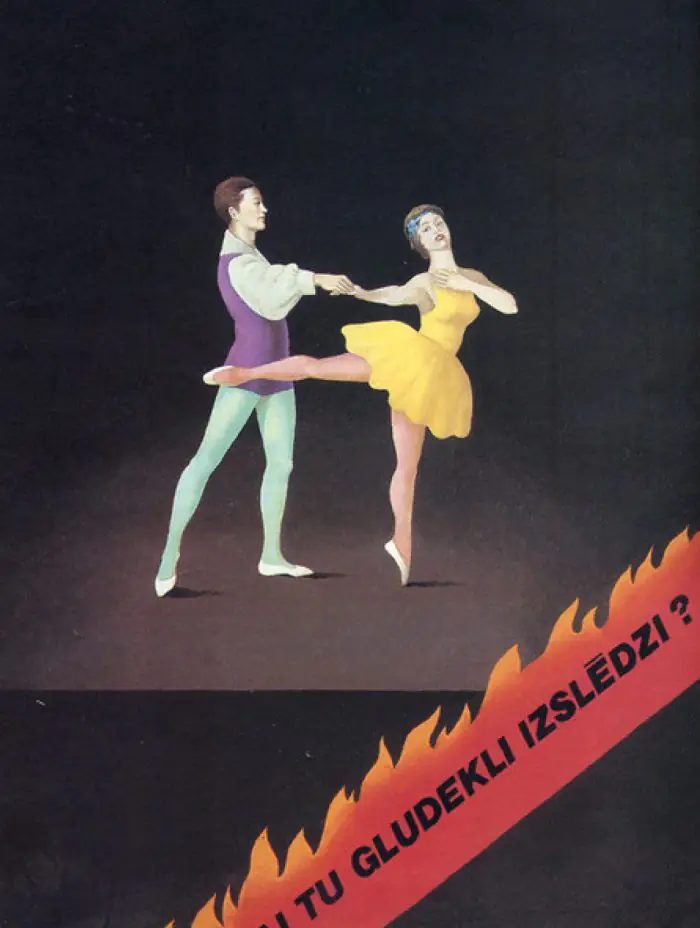

From the 1970s poster art received a new impetus: artists were increasingly commissioned to design posters for events, theatre and art exhibitions, as well as film premieres. This brought even more freedom, as poster artists could incorporate more complex and painterly techniques into their work, create references to different historical eras, and create stylisations far removed from the official framework.

liveinternet.ru

liveinternet.ru

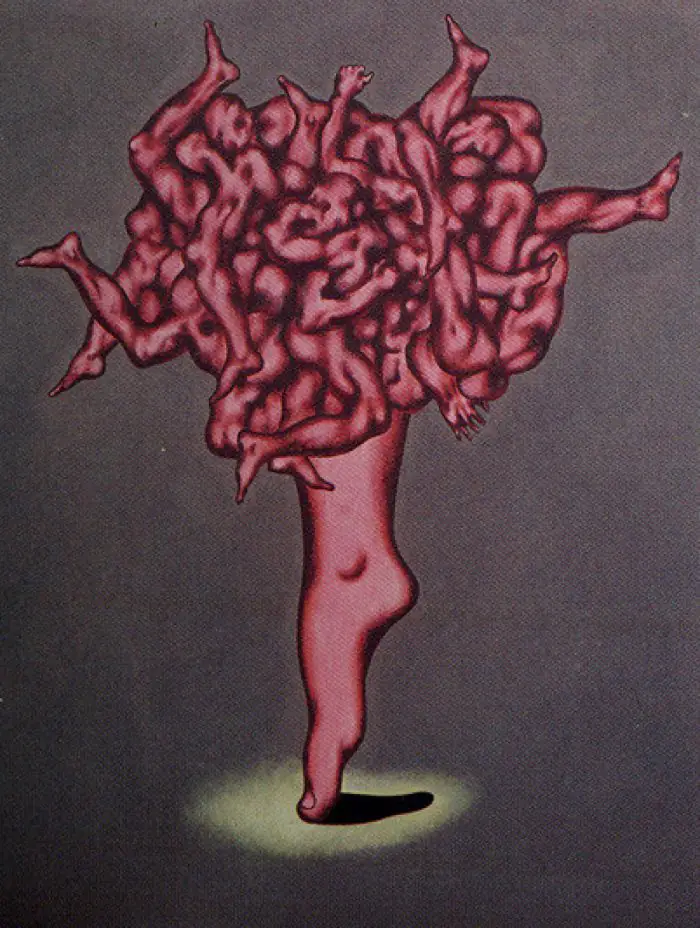

The decade before the collapse of the USSR is considered to be the time when Latvian poster art flourished: in the 1980s the images became increasingly complex and expressive, while the state’s control was loosening. From subtle aesthetic intellectual messages, artists increasingly gravitated towards politicised, harsh and straightforward statements.

However, after Latvia gained independence, the movement lost strength. Posters acquired a much more utilitarian role, and artists and designers were once again free to try out other means of expression.

Today the poster is unfortunately considered to be a dying art; this is recognised by both art historians and the poster artists themselves, many of whom are still alive and creating. Here’s how Gunārs Kirke’s daughter, poster artist Frančeska Kirke, talks about it:

“Dad gathered active people around him, generated ideas, and that’s how the then famous poster mafia was born. The times were bleak and gloomy, without any prospects for the future, but the poster provided a tremendous opportunity to express oneself in the parsimonious language of Aesop. Everything that was happening to Dad was impossible neither before nor now, only there and then; nowadays the poster as a genre is dead.”

digitalabiblioteka.lv

fold.lv