Photo: Asya Zolnikova

The National Museum, or ENM, is the largest cultural object in Estonia. The building occupies 34 thousand square meters, the collection includes 140 thousand items, including hundreds of folk costumes, everyday objects and works of applied art.

Despite its importance, the museum is not located in Tallinn, but 190 kilometers from the capital, in Tartu, the second largest city in Estonia. At first glance, it may seem that the building looks even too neutral for a national museum: simple and minimalistic composition, modern materials, delicate interplay with the landscape—the monolithic volume ‘floats’ above the cascade ponds, which have been preserved here since the early 20th century.

But it is the serene tone that can be traced in both the architecture and the exhibition that allows us to talk about the Estonian national character, the country’s recent grim past and its current aspirations for the future.

Working with the past

Like other countries in the Baltic region, Estonia entered a period of national revival in the 19th century. During this period, the heroic epic “Kalevipoeg” was published for the first time, which, like the “Kalevala” in Finland, significantly influenced the Estonian nation’s self-image and culture. National motifs were increasingly used in architecture, painting and other arts. In 1909, a national museum dedicated to the legacy of Estonian folklorist Jakob Hurt was established in the city of Tartu, known primarily for its university.

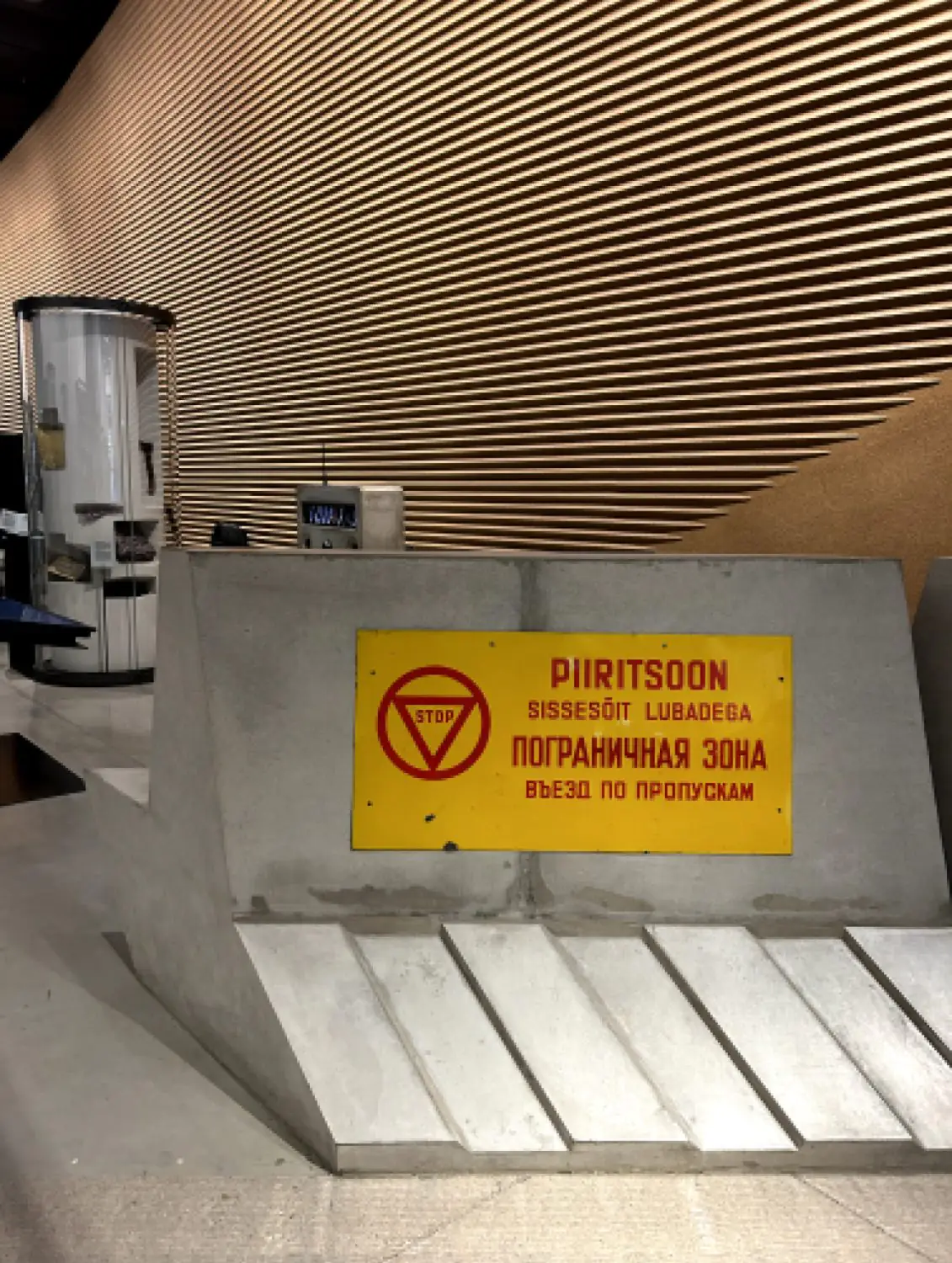

After the First World War, the museum found its first permanent home in the Raadi estate, where the Lipgarts, Baltic Germans, lived. Today, only the ruins of the manor house remain—they are located next to the modern museum building. In 1940, the manor and 100 hectares of land around it were confiscated by the Soviet Army, which opened a military airfield here. In 1944 the manor was bombed during the Tartu offensive. After the beginning of the Soviet occupation, the blue, black and white flag and other national symbols were banned, and the revival of the museum was out of the question.

Tartu remained a closed military city till 1990. During this time, the museum’s collections were stored in churches and other empty buildings. At the end of the 1980s, the call to rebuild the museum became part of a new campaign for Estonia’s freedom and independence from the Soviet Union. After regaining independence, years of debate, and joining the European Union, the country finally announced a competition for a 70-million-euro building in 2004.

The architects of the Paris-based studio DGT won the competition. The name is derived from the first letters of the founders’ surnames: Italian-Israeli Dan Dorella, French-Lebanese Lina Gotme, and Japanese Tsuyoshi Tane. Before founding DGT, they worked in the London offices of David Adjaye and Norman Foster. Sacrificing sleep and rest, they created the competition entry in their spare time.

When the results were announced, partner Lina Gottme returned from a trip to Paris. She recalls: “I was standing in front of the Centre Pompidou … the outstanding story of its young architects leading this utopian project into realization. At that moment, I got a call and learned that we had won the Estonian Museum project”.

Building is a gesture

The young age of the authors is not the only thing the Pompidou Museum and the Estonian National Museum have in common. As with the Paris building, the architects came up with a truly audacious solution. Instead of using the competition site in the center of Tartu, DGT proposed to return the museum to the then defunct airfield—in other words, to build a new national symbol on the “ruins” of a tragic past. The architects believed that in this way the museum would play a significant role in the revitalization of the neighborhood, infusing it with new energy and meaning.

At each subsequent stage of the project, obstacles awaited. Part of the Estonian establishment insisted on building in the center of Tartu or in Tallinn, and also objected to the participation of foreign architects. The European Union refused to provide grants for the construction because officials were not satisfied with the remoteness of the former airfield. The economic crisis of 2008 significantly affected the pace of construction.

Photo: Asya Zolnikova

Nevertheless, the project was realized exactly as the architects intended. They attribute the “miracle” of realization to former director Christa Aru—”the strength of this woman”—as well as their own faith and perseverance: “we were ready for anything to make this happen”.

It was hoped that the importance of the site itself would solve the accessibility problem. In general, these hopes were fulfilled: in the first two months after the museum’s opening in 2016, 60,000 people visited the exhibition. The project was soon awarded the Grand Prix FX, a prestigious prize in French architecture.

The ENM’s main building is a rectangular volume 355 meters long. The glass walls are topped by a sloping roof with a large walkable canopy. The “soaring” silhouette and massiveness of the building is both a reference and an extension of the runway, as well as a metaphor for the launching pad for endless possibilities that lead to the sky.

The main entrance is located at the front and is recessed into the tallest part of the building, which reaches a height of 14 meters and plunges into the ground like a shard of ice. Upon entering the building, the visitor sees rows of halls separated by glass walls from each other and from the street space—the journey through the ground floor of the building is perceived as a journey through an uninterrupted landscape. The fully glazed facades of the exterior side walls are covered with an abstract motif of the cornflower, Estonia’s national flower. According to Gotme, this pattern also refers to snow and “delicately breaks up the monumentality” of the building. The result is a contrasting blend of the national and the international, the folkloric and the modern.

Thus the very building of the national museum communicates more about Estonia than any of the objects presented here. “If Russia were to invent such a thing now, it would look like another form of aggressive aggrandisement; if Britain, an episode of querulous post-Brexit blue-passport patriotism; if Germany, it would raise issues too agonising for a single museum to handle”—wrote the British architecture critic Rowan Moore. Estonia, with its 1.3 million population and two periods of independence lasting just over 50 years, is a different matter.

Exhibitions

At the ticket office you can choose one of seven languages (Estonian, English, Russian, Finnish, Latvian, German, French)—this is necessary to translate the signatures on the text screens at the exhibits using a chip on the smart ticket. Watch the video to see how it works.

The two main expositions are organized in this way—the permanent exhibition “Encounters” about the everyday life of Estonians and “Echo of the Urals” about the language and life of the Finno-Ugric peoples.

Photo: Asya Zolnikova

Photo: Asya Zolnikova

Photo: Asya Zolnikova

Photo: Asya Zolnikova

The halls of the “Encounters” are very different in content and form—there are large thematic expositions devoted to this or that phenomenon, and nooks, darkened rooms for film screenings and interactive installations—you can, for example, “tune in” a Soviet-era radio. In this case, the game format not only entertains visitors, but also helps them immerse themselves in the cultural landscape and rethink its meaning. According to architect Gotme, this physical act of ‘digging’ into content symbolizes DGT’s approach to understanding the design problem: “whether a museum, an interior or set design, it is a digging process. A dig for histories, for stories, for traces …”.

Photo: Asya Zolnikova

Photo: Asya Zolnikova

Photo: Asya Zolnikova

The aim of the museum is not so much to record historical events as to depict the lives of ordinary people, which is why there is space not only for Estonia’s great achievements and symbols, but also for everyday objects: jeans and plastic bags (the main “fashion” of the late Soviet period), furniture, crockery, utensils and food packaging. Each item on display is accompanied by texts about the people to whom the objects belonged.

The museum also has several temporary exhibitions. The current one is “Who Claims the Night?” about Estonian nightlife from the Middle Ages to the present day; it runs until February 24, 2025. In the largest temporary exhibition hall, a solo exhibition of Ryoji Ikeda, an internationally renowned Japanese composer and artist, opens on November 2. The exhibition “Surrealism 100. Prague, Tartu and other stories…”—it was part of the big program of Tartu as the European Capital of Culture.

Other ENM exhibition spaces are located at Raadi Manor, next to the main building, and at Heimtali Museum, a branch of ENM in Viljandimaa County. In the future, the program will include traveling and virtual exhibitions. In addition, people and civic associations that are not involved in museum or curatorial activities can exhibit at the museum. Every year the museum announces a competition for the best “amateur exhibition”; in 2025 it will be dedicated to books.

In addition to the exhibition rooms, the main building houses workshops, a learning center, a library with archives, and storage facilities. A restaurant and a large Estonian souvenir shop are available for visitors.

Good to know before visiting

- This is a really big museum that you can’t get around quickly. We recommend that you set aside at least half a day to visit it.

- A standard ticket costs €15. It gives you unlimited access to all the museum’s exhibitions for one day.

- From the center of Tartu, the easiest way to get to the museum is to take bus number 7 and get off at the ERM stop. From the railway station, bus number 25 stops right next to the building

Estonian National Museum

60532 Tartu, Estonia

Exhibitions, restaurant and museum shop are open Tuesday-Sunday, 10:00-18:00.

Photo: Asya Zolnikova