Architecture before 1917

The specific geographical location of Daugavpils determined the diversity of its religious composition. From 1791 to 1917, the city and Latgale as a whole belonged to the so-called Pale of Settlement—a territory outside of which Jews were prohibited from permanent residence (with a few exceptions). For example, in the early 19th century, Jews made up about 57% of the population of Daugavpils. In 1921—around 40%. During the German occupation almost all Jews were killed.

The Kaddish synagogue building, constructed in 1850, has been preserved. The family of Mark Rothko—the famous artist born in Daugavpils—contributed financially to the restoration of this model house. Before the arrival of Nazi Germany, the city had around 45 functioning synagogues.

Because Daugavpils is located in Latgale, unlike northern and western Latvia, the region has many catholics—a result of Polish and Lithuanian influence. We recommend visiting two catholic churches: the Roman Catholic Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary on Church Hill, built in 1905 in the Neo-Baroque style, and the Saint Peter’s in Chains Roman Catholic Church, reminiscent of a small version of the Saint Peter’s Basilica Vatican City.

Church Hill is also home to the Neo-Gothic Martin Luther Cathedral (1893), the Orthodox Saints Boris and Gleb Cathedral (1905) in Neo-Russian style, and he Daugavpils First Old Believer Community’s Prayer House (1928)—many Old Believers still live in Latgale today.

The present appearance of the city center was largely shaped at the turn of the 19th–20th centuries, when Art Nouveau architecture was fashionable.

chayka.lv

A representative example can be found at 55 Saules Street. This building, with residential premises on the second floor and public spaces on the first, is recognized as an architectural monument of national significance. Its façade is richly decorated with mascarons, atlantes, an eagle sculpture, a lion’s head, gypsum wreaths, and other decorative elements.

No overview of the city would be complete without mentioning the Daugavpils Fortress, whose construction began in 1810—a reaction by Russian Emperor Alexander I to Napoleon I’s aggressive policies. Over its more than 200-year history, the fortress was reconstructed several times and supplemented with new structures, serving various functions.

For example, from 1948 to 1993 it housed the Daugavpils Higher Military Aviation Engineering School named after Jānis Fabriciuss. In the post-Soviet years, numerous reconstruction projects were proposed, but only in 2013 did the Mark Rothko Museum open in the former artillery arsenal building—dedicated to the famous abstract artist born in Dvinsk (the city’s name at that time).

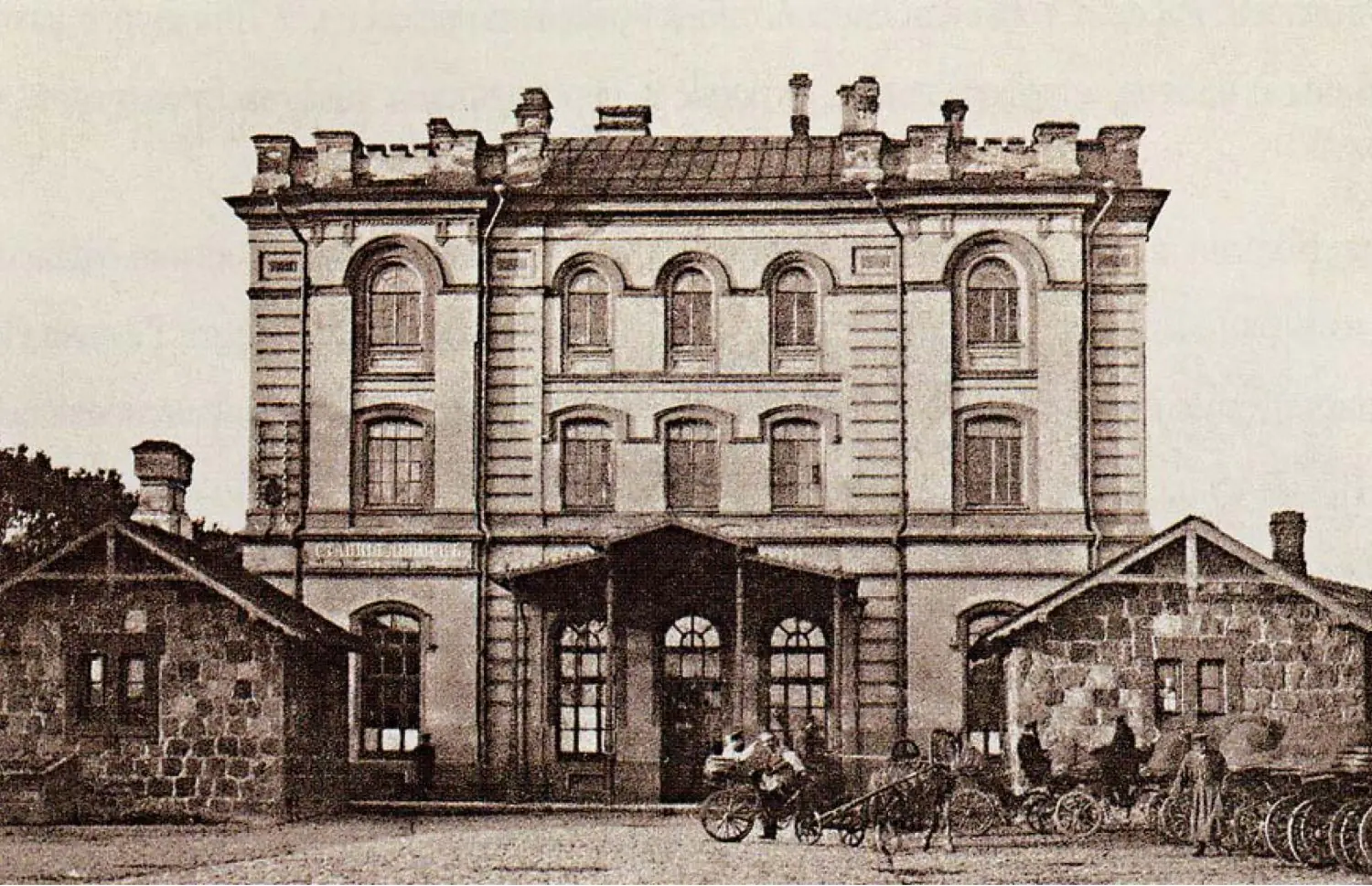

One of the greatest losses of architectural heritage was the Saint Petersburg–Warsaw Railway Station, built between 1874 and 1878. It stood until 1944 near today’s 1 Zeltkalna Street. However, the destruction of the building had begun even before German troops entered the city during World War II. It was also damaged during World War I, and in the late 1930s it was partially dismantled due to a decline in railway traffic along that route.

1918–1940

In the 1920s–1930s, Latvian architecture sought a national style. The popular Art Deco of that era was taken as a basis and combined with elements of traditional ornament and even vernacular architecture. An outstanding example of such architecture is the Unity House (Vienības nams), built in 1937 according to the design of architect Verners Vitands.

This multifunctional building housed a theatre, a Latvian society, a library, and other public institutions. Today it also hosts a tourist information center and a museum dedicated to šmakovka—a traditional Latgalian alcoholic drink.

The restrained yet monumental architecture of the building is well expressed in the geometry and decor of its façades. But the interiors are also worth exploring—especially the auditorium of the Daugavpils Theatre, located within the Unity House. The expressive curving lines of the ceiling, balconies, and stage are unforgettable at first glance and provide a clear impression of Latvian and global architecture of the 1930s.

1945–1990

In the post-war years, Latvia was occupied by the Soviet Union. While Western and Central Europe turned toward modernist architecture in the late 1940s, the USSR continued to favor Neoclassicism—often called Stalinist Empire style—until 1955.

In 1955, just as Nikita Khrushchev began his “fight against excesses” in architecture during the de-Stalinization period, the Daugava Cinema opened at what is now 53 Viestura Street. It was housed in a new building reflecting classical notions of beauty: strict symmetry, a grand portico decorated with Corinthian order columns. Today the building serves as a club.

The period from the 1960s to the 1980s is characterized predominantly by modernist architecture, tending toward standardization and internationalization. During this time, new residential districts with standardized housing blocks of various series were built in Daugavpils. They are an integral part of the city’s visual identity and can be considered historical heritage. To this day, a significant number of residents live in these buildings.

One of the largest constructions of that era is the Latvija Hotel (now Park Hotel Latgola), built between 1975 and 1985. It is a typical modernist project, concise in form and rational in content. The current appearance of the hotel differs from the original—the result of renovations carried out 20 years ago.

Contemporary architecture

In the late Soviet period and the first post-Soviet decade, regionalism became the most popular architectural direction. It focused on searching for local artistic specificity—a kind of modern Latvian style. Designers actively used folk ornaments, elements of traditional architecture, and reinterpreted the heritage of various historical eras: from the Middle Ages to the Ulmaņlaiki period (the 1930s) and later times.

An interesting example of synthesizing old architectural traditions—rethought in a slightly playful postmodern spirit—can be found at 46 Krāslavas Street. Here you’ll find pitched triangular tiled roofs, bay windows, openings of various shapes, niches, and extensive use of classic materials such as red brick. The building was constructed in the early 1990s. For many years it housed the Russian consulate, which was closed in 2022 due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Around the same time, near Lake Stropu on Mēness Street, a row-house quarter of small townhouses was built. In Latvia, unlike in many other former Soviet republics, such housing had already been common in the 1970s–1980s, but in the post-Soviet era it gained even greater popularity because it was associated with a Western lifestyle. We wrote more about architectural developments of the 1990s–2000s in the article on capitalist romanticism.

In the 2000s, amid rapid economic growth, architectural trends shifted. Architects moved away from regionalism and contextualism toward what is known as high-tech architecture. This style is less interested in local traditions and more aligned with international fashion.

A vivid example of Daugavpils high-tech architecture is the Ditton shopping center (formerly Ditton Nams), built in 2002. Its appearance is bright and eye-catching, though poorly integrated with the surrounding historical buildings. This effect is reinforced by its materials: metallic façade panels, continuous curved glazing at the street corner, and a decorative “diadem” supported by metal columns.

In the 2000s, buildings from the Soviet period were often renovated—both in Daugavpils and other Latvian cities. A representative example is the hotel Latvija (now Park Hotel Latgola), originally built in a modernist style in 1975–1985. In the 2000s it was reconstructed, modernizing both the interiors and façades. A huge stylistically typical arch was added to the roof, and a shopping center was integrated into the lower floors to ensure the ground-level space would not remain underused.

A significant portion of Daugavpils architecture built during the 1990s–2000s was designed by the architectural office Arhis.

The period of rapid market growth in the 2000s ended with the global economic crisis, which also affected architecture. Visually expressive—but often wasteful or daring—experiments were replaced by greater simplicity, inspired by pre-war and post-war modernism.

A characteristic example of 2010s architecture is the new building of the Daugavpils design and art school named Saules skola (Saules school). Constructed between 2017 and 2021, it acts as a sort of ceremonial façade of the city for everyone entering the central part via the Unity Bridge (Vienības).

In the 2010s, urban development received increasing attention. Over the past decade, many streets and green zones in the city have been renovated. Among them, the Stropu Lake promenade stands out in particular—we recommend it to everyone visiting Daugavpils.

You may also want to read the Neighborhood guide to cultural places, cafés, and restaurants of the city.