The Flâneur: More Than Just a Passerby

The concept of the flâneur emerged in the 19th century when sociologist Georg Simmel described life in large cities. He observed that Parisian residents, immersed in the metropolis’s hustle and bustle, seemed to become part of a gigantic spectacle. The city, he noted, entices with its novelty, offers a sense of freedom, yet simultaneously seems to trap individuals within their own experiences. A flâneur isn’t just someone who walks through the city; they generate sensations, perceiving space through the lens of personal experience.

vitber.com/en/lot/14668

In his essay “Urbanism as a Way of Life,” Louis Wirth begins with the words: “What happens in the city concerns all of us.” In this sense, we are all a bit like urban environment experts, flâneur-observers of urbanization as a process of social restructuring, where humans act as the central dynamic force. We are both participants in and objects of these changes. Even a short walk is a form of “walking rhetoric,” an appropriation of space through movement.

In this article, we’ll look at the city through the eyes of the flâneur, uniting a diverse group of city dwellers who perceive a walk without a specific purpose as a practice of everyday life. We will explore how walks alter our perception of the city’s fabric, how we appropriate space, and how we create unique stories and mental maps of the urban landscape.

The Many Faces of the Flâneur

So, who exactly are these flâneurs? They are not just idle gawkers, but active explorers of the urban environment. A runner inadvertently notices the changing landscapes, the rhythm of alternating parks and residential areas, and changes in landscape. A senior citizen holds memories not only of architectural shifts but also entire layers of recollections and associations, charting the evolution of space on a semantic level. A mother with a stroller, choosing convenient routes, observes details unnoticed by others: ramps, sidewalk widths, the placement of benches and shops. The classic flâneur, for whom the walk itself becomes the purpose, and the city is a text they read with their steps.

Walter Benjamin saw the phenomenon of flânerie as a way to resist the depersonalizing forces of industrialization and commodity fetishism. The city was a “phantasmagoria”—an illusory world, enticing with novel impressions, yet simultaneously trapping individuals within their own experiences. The flâneur, immersed in this stream of images, might consider themselves a consumer of the city’s art, but in reality, they become part of this spectacle.

The City on Your Personal Map

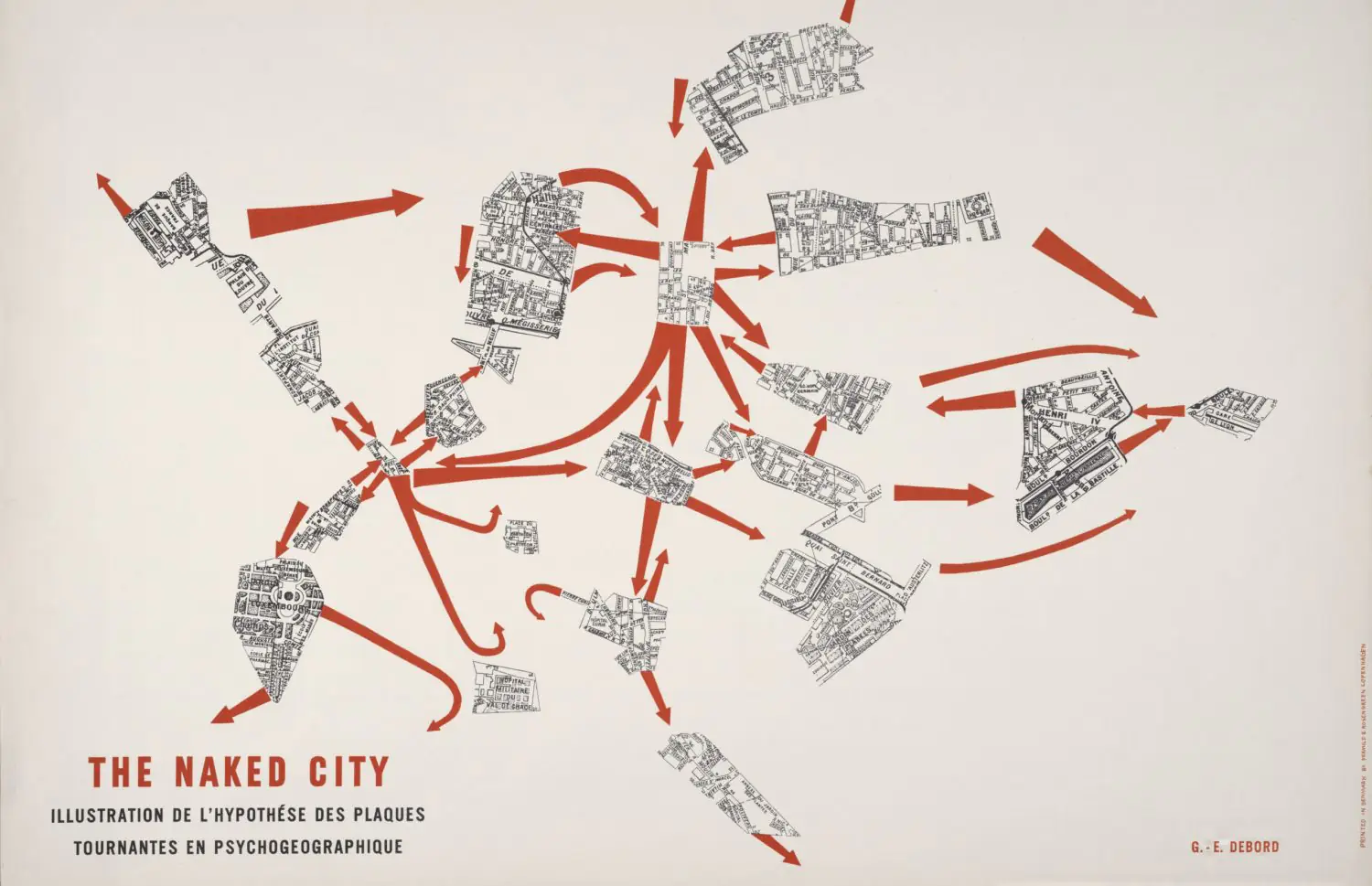

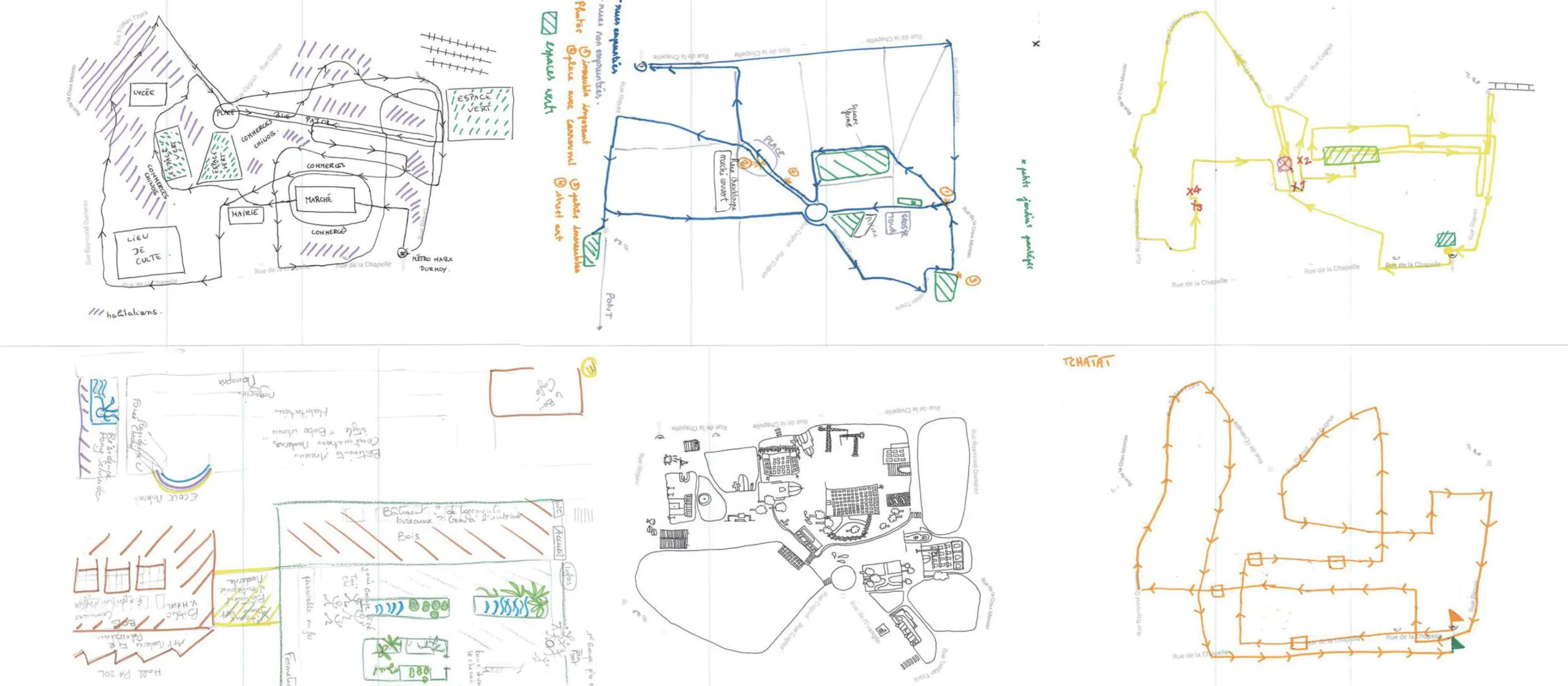

Imagine your favorite walking route. It likely doesn’t look the same in your mind as it does on Google Maps. Situationists proposed creating mental maps of their journeys to understand how the city affects our emotions.

onlineexhibits.library.yale.edu

The concept of “psychogeography” aimed to uncover the city’s hidden emotional landscapes through practices like “dérive”—aimless wandering through the city, driven only by spontaneous desires. Guy Debord’s “The Naked City”—a psychogeographical map of Paris, composed of fragments of different maps connected by arrows—visualized these impulses and movements.

Mental maps are more than just navigational tools. They reflect personal experience, emotional connections, and interpretations of urban space. Space filtered through imagination cannot remain indifferent. Each of us creates a unique map of the city, woven from personal experiences, impressions, and memories.

frontiersin.org

In “The Practice of Everyday Life,” Michel de Certeau contrasts “strategies”—the authoritative ways of organizing architectural space—with “tactics”—ways of consuming space by resisting the givenness and alienness of urban environments through which panoptic structures attempt to regulate citizens’ lives. Flânerie is one such tactic. A flâneur has no fixed place in the static hierarchy of urban planning; they act fragmentarily, seizing opportunities that arise spontaneously. Their movement transforms circumstances into “chances,” much like a child’s imaginative play with contexts and narratives.

A walk through the city is a kind of “speech act” by the pedestrian, a metaphor for narrative, a dream of the road. Each step, each turn, is a “word” in the language of urban movement. The flâneur chooses some possibilities, ignores others, creating a “story” in space.

The City’s Invisible Stories

The pedestrian’s stride imprints its own story, imperceptible to static urban structures, because it improvises, engaging with time and movement. Here, two important “rhetorical figures” of pedestrian movement can be identified: synecdoche and asyndeton.

Synecdoche manifests when the flâneur perceives an iconic architectural element as a symbol of an entire neighborhood.

Asyndeton, the omission of connecting elements, is reflected in the fragmented perception of the city during a walk, where attention latches onto individual details, skipping entire sections.

In a consumer society, objects often lose their utilitarian value, becoming signs that express status and identity. This applies to urban spaces as well. Walking through the city, we don’t just see buildings and streets; we read these signs, interpret them, integrating them into our own system of meanings. Architecture becomes part of the exchange of signs, transmitting specific messages about power, culture, and history. These signs influence our sense of comfort through the interplay of rigor and coziness, privacy and publicity, order and chaos.

Imagine the city submerged in a web of invisible routes, each composed of atoms of stories and impressions. For one is an ordinary staircase might be a springboard for a cyclist, a resting place and lively conversation spot for children, and an annoying inconvenience for a woman with a stroller. These are entirely different impressions and maps of the same object! Everyone has filtered the staircase through the prism of their imagination and depicted it in their own emotional and narrative style.

Space as Personal Experience

The city lives not only in stone and glass but also in the elusive dance of its inhabitants’ daily steps. Every walk becomes an act of deconstruction and reinterpretation of urban space. People, driven by their goals and desires, imperceptibly erase some parts of the city from collective consciousness and, conversely, imbue others with special meaning, distorting the strict geometry of plans and breaking the usual order.

To walk is to experience a lack of space. The movement that the city multiplies and concentrates makes the city itself a vast social experience of this lack. Walking can be extroverted, when it becomes a way of going outward, exploring the unknown. And introverted, when the mobility of our thoughts and feelings moves beneath the seeming stillness of the surrounding world. Symbolic mechanisms—legends, memory, and dreams—organize our perception of urban topoi, escaping strict systematization.

Personal stories, memorable places, and profound sensations form the connection between our walks and their meaning. Stories form spatial trajectories, imbuing the city with a narrative structure.

The City as a Living Text

A walk through the city, in all its diverse forms, is a unique meditative and exploratory experience. The flâneur actively interacts with the architectural environment, appropriating and mastering it through movement. These everyday practices create a rich palette of urban narratives, shape our mental maps, and allow us to see the city not as a static collection of buildings and streets, but as a living, dynamic text that we write with our steps. Every walk is a small journey, filled with discoveries, memories, and personal meanings, making us not just inhabitants, but active co-creators of urban space.

What’s your favorite “story” of the city that you’ve “written” with your steps?