Photo by Tomaļunas Matīss

redzidzirdilatviju.lv

Kiosks during times of empire

Riga’s historic kiosks were more than just places of sale – they were carefully designed elements of urban space, combining functionality with aesthetics. The first kiosks, often called pavilions, appeared in the early 20th century as a municipal initiative to organise street trading and make it visually appealing. They were placed in prominent locations – gardens, boulevards, bus stops – and integrated into the surrounding architectural environment.

dom.lndb.lv

These pavilions served not only for trade, but often also as tram stops, public toilets or warehouses. Some of the most striking examples of this type of architecture in the streetscape of Riga are the kiosk on Miera Street, designed by the Riga city architect and author of the Agenskalns Market Reinhold Schmaeling and the kiosk on Tērbatas Street, designed by the architect Wilhelm Rössler.

facebook.com / Par Āgenskalnu

redzidzirdilatviju.lv

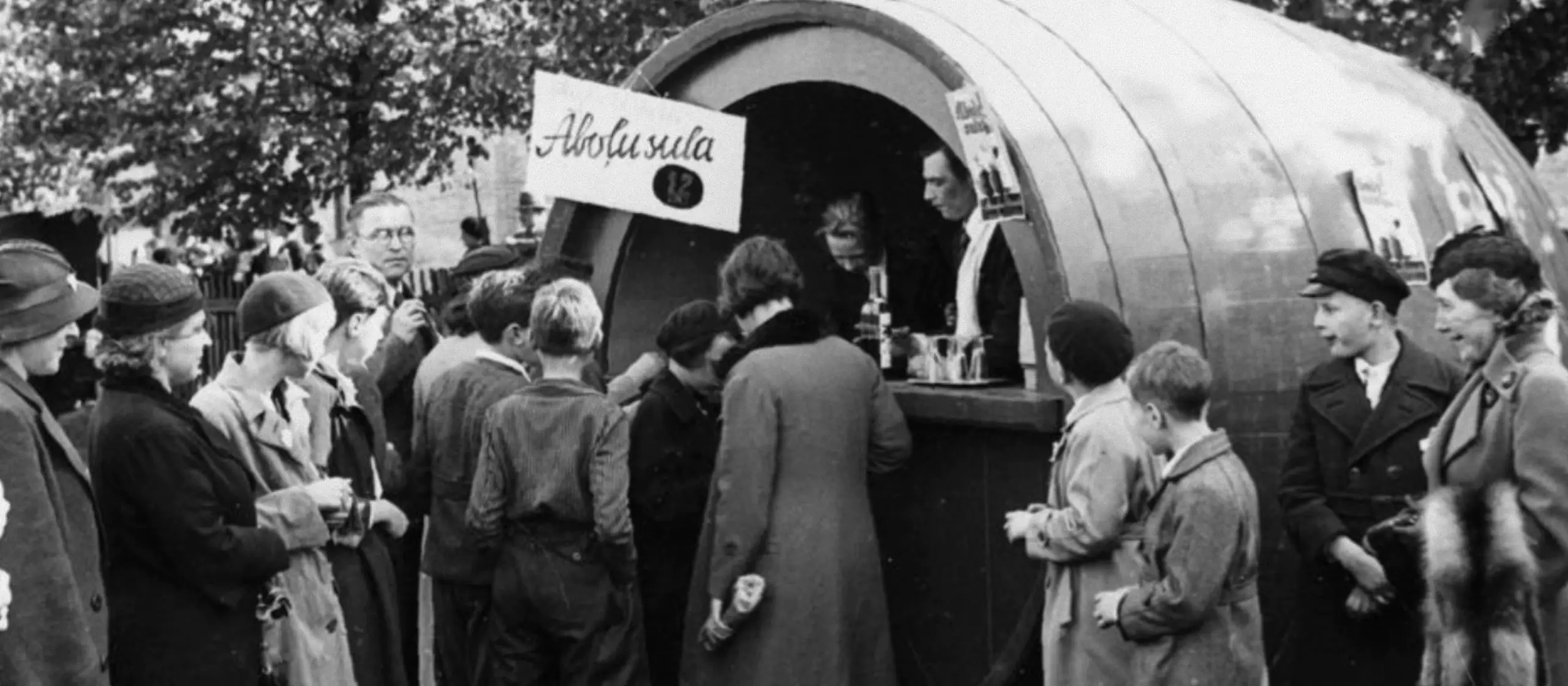

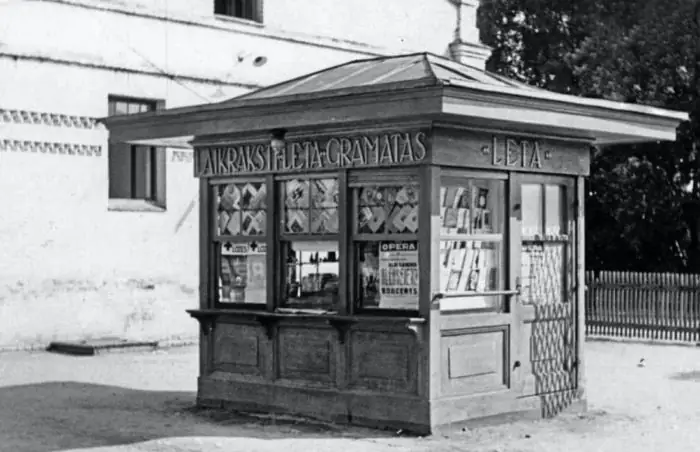

Kiosks in interwar Riga

During the interwar period, the city of Riga continued to actively incorporate kiosks into the urban environment. The development of kiosks is closely linked to the expansion of the railway network: newspaper outlets appeared in and around stations, offering passengers the opportunity to pass the time and shop. Seasonal wooden kiosks, mainly selling fruit, became increasingly popular, but the city also continued to build permanent, architecturally distinctive kiosks. One of the most striking examples that has survived is the Kolonāde Kiosk (1924), designed by architect Arthur Mödlinger. The kiosk functioned as a newspaper outlet, a tram stop and a public restroom. Today it houses a restaurant which has kept the historic name.

meetriga.com

Kiosks in soviet Riga

During the Soviet period, a completely different approach to kiosk construction was introduced into Riga’s urban environment – individualised architectural solutions were replaced by serial, standardised constructions. Architects adapted these standardised kiosks to local needs. They were simple, functional volumes – metal, plastic or wooden structures that could be quickly installed and easily moved. During the Soviet occupation, a number of kiosks built between the wars were modified or demolished to adapt them to the new ideological environment.

instagram.com / historyofriga

For example, the intersection of Brīvības and Elizabetes Streets was once home to a kiosk with an impressive advertising pole. The Soviet authorities chose this site for the Lenin statue, thus not only physically replacing the city’s commercial space, but also symbolically replacing the capitalist values of the inter-war period with Soviet ideology.

Many of these kiosks lost their original function after independence – they were dismantled, converted or simply abandoned. In some cases, they found new uses as, for example, parking wardens’ huts, guard posts or warehouses. Today, their presence in the urban landscape seems more often like a fading witness of an era than an active part of the urban space.

Redzi, dzirdi Latviju

One of the most striking examples of the transformation of Soviet-era kiosks in contemporary Riga can be seen in the gardens of the Sports Palace, where a typical metal kiosk was adapted as a cultural and community space. Under the direction of architect Monika Varšavskaja and artist Darja Melnikova, it became part of the Palette project: a place where art events and other activities took place in an informal setting.

Photo by Gustavs Grasis

satori.lv

Photo by Gustavs Grasis

satori.lv

By preserving the original material and structure of the building, the kiosk served as an example of how a historic, utilitarian object can be transformed into a viable, contemporary element of urban space.

facebook.com/Sportapilsdarzi

From utilitarian object to community place: kiosks today

After the restoration of Latvia’s independence in the 1990s, a new, often spontaneous layer of temporary architecture began to emerge rapidly in Riga’s public space. Dozens of small kiosks, huts and commercial pavilions, both legal and self-built, appeared in the new market economy – especially at Riga Central Station, the bus station and the Central Market.

These structures served as small trading places and at the same time created a chaotic but characteristic environment for the city and the times. Although functionally temporary, these structures embodied the spirit of an era of change and animated a new, free use of urban space that often took place outside any planning framework.

At the turn of the 1990s and 2000s, typical kiosks with glass windows appeared in the urban environment and quickly became a familiar part of the cityscape. They offered quick and easy access to everyday necessities, but in recent years these kiosks have gradually disappeared, giving way to retail outlets on the ground floors of buildings. This shift reflects not only a change in consumer habits, but also a new approach to planning the city environment.

The municipality is gradually re-engaging in the development of temporary architecture. For example, in the spring of 2024, a project featuring standardized modular units designed by architect Toms Kampars introduced new, uniformly designed street market stalls.

This structured, municipality-led architectural approach was chosen to replace outdated structures and organize micro-commerce in several neighborhoods, with plans to install up to 64 modules in the coming years.

The example of the Central Market draws attention. Here, unauthorized construction was halted through direct intervention by the building authority, and the property owner (the municipality) had to address the consequences of this spontaneous development.

Overall, these processes reflect a shift from unregulated, free-form construction to a more thoughtful and sustainable implementation of temporary architecture. Kiosk chains are relocating into ground-floor premises of buildings, avoiding the construction of new kiosks. This development signals a strengthened municipal effort to integrate kiosks and commerce into public space — while also prioritizing design quality, user convenience, and the city’s identity.