Leading urban analysis expert Anders Sevtsuk grew up in the Estonian city of Tartu. As a child, he lived in social housing, and this experience became the basis for his quest to create cities that are centered on people and their needs.

“Your home was where you slept, but everything else, where you played as a child or found cultural entertainment as a teenager, was in the public sphere of the city.”

linkedin.com

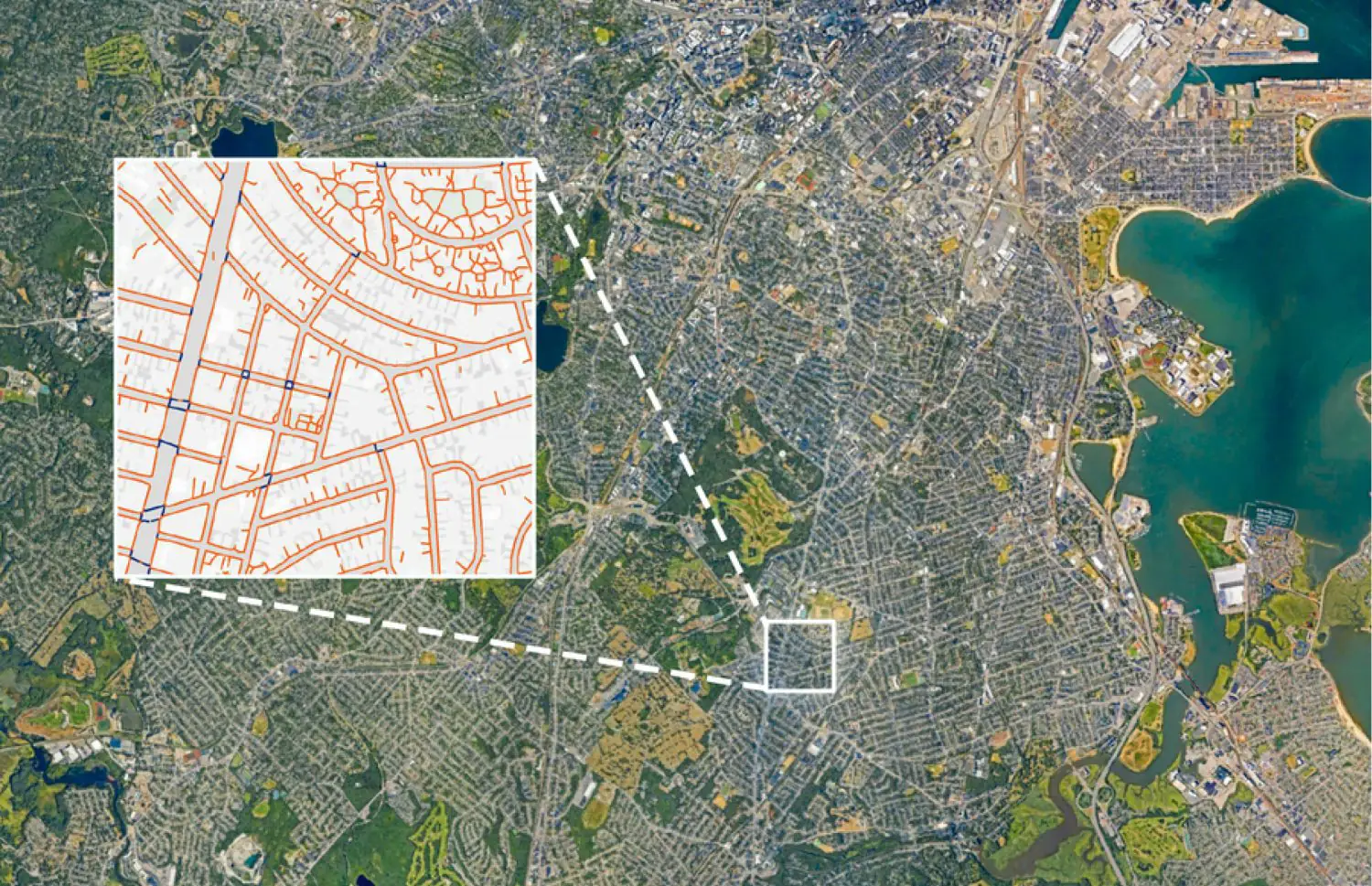

He leads the City Form Lab at MIT, which focuses on urban planning, mobility and urban design research. The lab’s innovative pedestrian activity models take into account factors such as pavement width, commercial space on the ground floors of buildings, and street landscaping.

These models have been successfully implemented in locations around the world, including Melbourne, Beirut, and New York. They can predict the effect of changes in the urban environment on pedestrian behaviour. A notable accomplishment of the Sevtsuka team was the development of the publicly accessible TILE2NET tool, which creates maps of urban pavements using aerial photographs. This tool provides planners and architects working in environments with limited access to the pedestrian environment with valuable data.

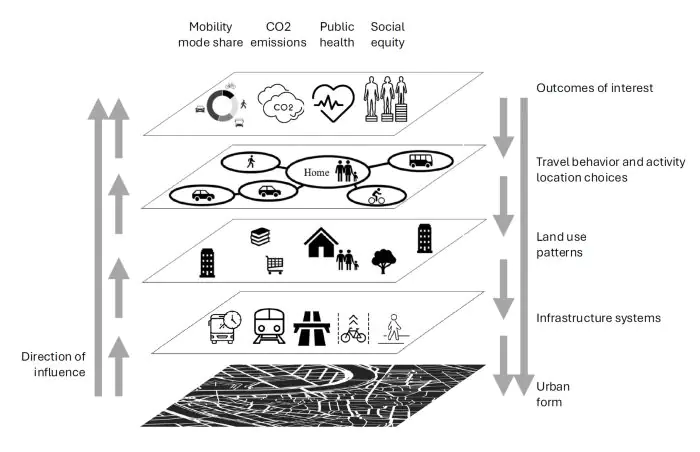

The City Form Lab interprets the city as a technological system consisting of three main elements: tools, services, and infrastructure. This system largely determines citizens’ behaviour. Based on the shape of cities, infrastructure solutions and land use patterns, people will prefer certain routes, places to live and work. These daily choices are directly linked to carbon footprint, physical activity levels and mobility. Quality of life is higher in environments that are primarily pedestrian-oriented. Such environments not only improve the health of residents and reduce carbon emissions, but also strengthen the social connections that form the foundation of a democratic society.

The urbanist believes that there has recently been a shift in urban planning, moving away from urban design as a central focus area towards more sociologically and community-oriented approaches. At the same time, however, the last few decades have seen the creation of some of the most anti-urban, car-oriented cities in the US, with which we now need to work.

flickr.com / Rīga

Main conclusions

Carbon and density: numbers and insights

Sevtsuk explains that building density is linked to environmental sustainability. For example, Houston (USA) has a population density of 1,398 inhabitants per square kilometre and transport emissions per capita reach 9.5 tonnes of CO₂ per year. In Boston, which has a population density of 5,400 inhabitants per square kilometre, this figure is 3.5 times lower at 2.6 tonnes per person. The same is true of energy consumption: the lower the density, the higher the heating and electricity costs

Anders Sevtsuk

Therefore, we can conclude that compact, pedestrian-oriented cities use resources more efficiently, encourage the development of public transport, and reduce the burden on the environment.

Five steps to a sustainable city

Sevtsuk set out five zoning and urban design principles that enable increased density.

- Zoning for individual residential development should be cancelled. This will increase urban density and the diversity of building types.

- Allow small-scale commerce ‘by default’ in all zones. Such a measure would revitalise the streets, stimulate the local economy and encourage people to explore the city on foot.

- Restrict the construction of shopping centres that encourage people to drive and prompt planners to build more roads and car parks. Instead, support street retail and small, neighbourhood-sized malls. Sevtsuk focuses on Tallinn exclusively: the Estonian capital has the largest amount of retail space per capita in Europe.

- Eliminate the mandatory minimum requirement for parking spaces. This would reduce construction costs and encourage more sustainable modes of transport. Sevcuk cites data indicating that parking spaces in San Francisco increase the cost of housing by an average of $50,000.

- Make high pedestrian accessibility the main goal and starting point of urban development. One of the main criteria for new construction should be easy access to the ‘basket of everyday needs’ (stores, schools, parks and transport).

TOD and AOD: two types of density

Sevtsuk suggests two ways of increasing urban density:

- Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) – dense development around public transportation nodes.

- Amenity-Oriented Development (AOD) – densification of neighborhoods where there is already a high concentration of services and public spaces.

He emphasises that high density does not have to be uniform, but should be strategically targeted at areas where infrastructure and demand already exist.

Urban policy instrument

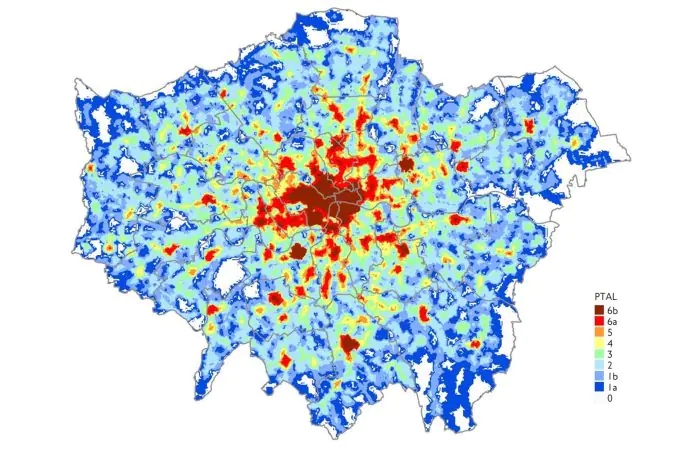

Examples such as the PTAL (Public Transport Accessibility Level) system in London and the model developed at MIT for assessing access to key functions (food, medicine, schools, transport, etc.) show that accessibility metrics can not only be used for analysis, but also form the basis for decision-making on urban development priorities.

International Transport Forum (ITF)

The more integrated a district is, the higher a priority it should be given when allocating investments.

The street as a nexus for sustainable development

In light of the challenges posed by climate change, inequality and urbanisation, Sevcuk calls for a rethink of cities as living organisms, where architecture, transport and infrastructure work together as a unified system. His approach is not just academic theory, but a practical guide to action: we should build more densely, with greater diversity and accessibility, in order to move away from an environment built for cars and return the city to the people.

fold.lv