When architect Daniel Libeskind began work on the MO Museum, his focus was on harmonising the building with its previous context. The site had been occupied since 1965 by the Lietuva Cinema, a typical modernist “box“ building that was common in cities throughout the USSR during the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras.

Although the cinema was popular and significant in the city, it was decided to close in 2005. The owner, who had privatised the building three years earlier, intended to construct a multifunctional complex in its place, complete with two cinema halls. However, four years later, the court stopped the demolition after numerous protests and petitions from citizens. However, the cinema was never reopened and remained abandoned until 2015.

commons.wikimedia.org

Then, in 2015, the MMC Projektai company announced that it would build a modern art centre on the site of the cinema. In 2017, “Lietuva“ was demolished and a time capsule was laid in its place. The Museum MO was then built within a year and a half.

Initiators

The museum’s foundation is considered to be one of the largest private art collections in Lithuania. Consisting of over 4,500 pieces, it covers the period from the 1960s to the present day. Since 2011, the collection has held the status of an object of national importance.

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

MO was founded by Viktor and Danguolė Butkus, a Lithuanian couple who are both scientists and entrepreneurs. Having collected contemporary Lithuanian art since the 2000s, they decided to not only acquire the collection, but also to exhibit it to the general public. They chose Pritzker Prize winner Daniel Libeskind to design the building.

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

“The basis of architecture is not concrete and steel, or the elements that make up the soil. Its foundation is a miracle,” says an architect.

Outside

Along with Zaha Hadid and Rem Koolhaas, Libeskind is considered one of the most prominent figures in deconstructivism. This architectural movement emerged in America in the late 1980s and represents a significant revision of modernism. It is characterised by broken lines and the individuality of each building.

Deconstructivism lends itself particularly well to cultural objects, including museums and memorials. Libeskind has a special place for these in his work — coming from a family of Polish Jews from Łódź, he has worked extensively with themes of the Holocaust and Jewish culture. His most celebrated works include the National Holocaust Memorial in Ottawa and the Jewish museums in Berlin and San Francisco.

Vilnius is home to his “smallest but most beloved” museum project, according to Libeskind. It was his first, and so far only, project in the Baltic States.

“It is really dear to me because I love this city — Vilnius and its people. Although Lithuania is a small country, it is special,” the architect said during the museum’s opening in 2018.

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

The Vilnius-based architectural studio Do Architects helped adapt the project to local architectural regulations. Even in the first steps, the architects attempted to establish a connection between the future building and the architectural traditions of Vilnius and classical architecture, thereby fostering a dialogue between the city and the arts.

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

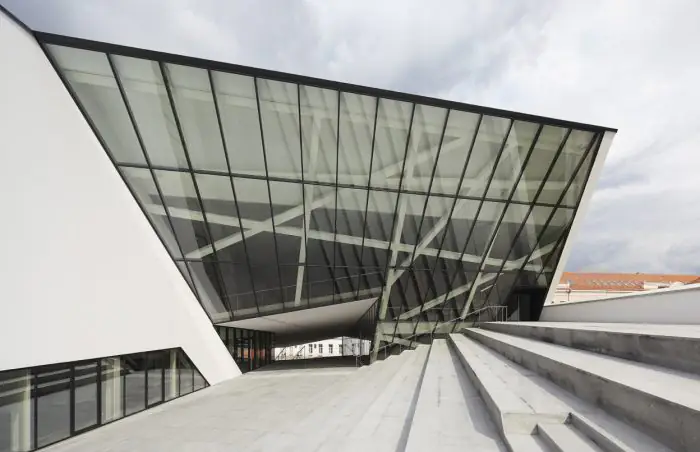

This gave rise to the idea of a cultural “gateway” connecting the eighteenth-century grid with the medieval town. The new building’s forms and materials are in keeping with the local architecture: its flat exterior façade is clad in white, low-maintenance plaster. This colour and texture distinguish the building from its dense historical surroundings while simultaneously referencing the modernist cinema that once stood on this site. An open staircase cuts diagonally across the outer corner of the museum. Recalling the hilly landscape of Vilnius, it leads to a public terrace that serves as a venue for performances and concerts.

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

The emphasis on public spaces is an important feature of the project. Almost a quarter of the site is occupied by green spaces, and a sculpture garden designed by winners of the Lithuanian National Prize for Culture and Art is located next to the building. The garden and terrace are open for free at any time of day.

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

Inside

Visitors enter the museum through a bright lobby with tall windows. The first floor features a lobby, an event room, a museum store, a café-bistro called “MO“ and an open art storage area. The exhibition rooms begin on the second floor, where there is a small exhibition space, a reading room, and administrative offices.

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

The main exhibition hall, which is designed to host MO’s largest exhibitions, is located on the third floor. This large open-air room can be divided by partitions if necessary. A spiral staircase resembling a DNA strand connects all three levels. This is one of the most photographed places in the museum and a symbolic reference to the founders past — Victor Butkas wrote more than 40 articles on the structure and modification of DNA.

According to Libeskind, this staircase is the first completely circular structure he has designed:

“I’ve never done this before — I’ve created curves, but I’ve avoided circles because they seemed banal to me. Anyone can create circles.”

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

However, in the case of the MO, it was the staircase that became the semantic center of the project:

“The spiral is the epicenter of the entire building structure. What is unusual is that the spiral is not an exact circle, it is spread out on several levels and is affected by what happens around it. It was very important to me that the angles of the images were appropriate.”

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

“This museum is unusual. It’s not just a white box – there’s light coming into it, the space is imbued with images of the city and people. This whole open-air theater – of streets and buildings – is important to me because it is a source of inspiration for art,” Libeskind concludes. The MO Museum, he says, is

“compact, spectacular and made for society, for its experience.” It is “a dialog between the simple and the complex, between symmetry and asymmetry, between abstraction and nature, between Vilnius and art.”

Around

MO has not only become an important cultural institution, but has also gradually transformed the environment around it. A public transport stop was renamed after it, and many establishments were opened nearby.

archdaily.com / Photo: Hufton + Crow

A few years later, improvements were made to the public garden adjacent to the building. As in the museum garden, it was adorned with artworks by Lithuanian artists. An artificial brook now flows through the square, reminding visitors of the spring that had been there since the 16th century and was used by the town’s residents until the Soviet era. Immediately after the square, a steep slope with striking relief begins. ID Vilnius’ architects used this feature to design a staircase with an intermediate terrace and viewing platform, from which you can enjoy a view of the Old Town’s rooftops.