The world is aging. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) and other international organizations, around 10–12% of the global population is aged 65 or over. Forecasts suggest this figure could almost double to 22% by 2050. Africa is the “youngest” continent, with a median age of 18.6–19.3 years, while Europe is the “oldest”, with an average of 44.7 years.

This is why designing urban environments with people with disabilities is not only a matter of social justice, but also common sense. If a city is built exclusively for the average healthy pedestrian, this constitutes implicit discrimination. Research shows that introducing an inclusive urban environment improves accessibility for many other groups, such as parents with prams, small children and the elderly.

Despite the urgency of the issue, adapting cities for limited mobility is a relatively recent phenomenon.

The beginning of barrier-free environments in cities

Following the Second World War, there were huge numbers of veterans in Europe and the United States who had suffered amputations or spinal injuries. It was this that first prompted people to consider architectural barriers. In 1963, American architect Selwyn Goldsmith published Designing for the Disabled, the first systematic work on designing inclusive spaces. This book became known as the “bible for practising architects”. In 1973, the United States passed the Rehabilitation Act, one of the first laws concerning accessible environments. The idea began to be discussed in Scandinavia and the United Kingdom, and standards for public buildings were introduced in Europe in the late 1970s.

design-milk.com

Gradually, the concept of an accessible environment expanded beyond individual buildings to encompass the spaces between them and the city as a whole, including streets, pavements and transport networks. By the end of the 20th century, inclusivity had become one of the most important markers of equality in cities. In 2006, the UN adopted the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, introducing the obligation to adapt not just individual buildings, but the entire environment — from transport to communications. Almost all European countries signed the document.

Successful cases

During the 2010s, awards, rankings and international conferences dedicated to accessible cities emerged, such as the Access City Award, which was organised by the European Commission and the European Disability Forum. This brought the concept of an accessible environment into the spotlight and helped to showcase successful examples.

In 2024, for example, the Spanish city of San Cristóbal de La Laguna received the Access City Award. The jury noted that most public buildings were barrier-free, and that people with disabilities had access to transport and, crucially, the city centre. This demonstrates that it is possible to make the environment comfortable for everyone, even in historic neighbourhoods with narrow streets and uneven terrain.

In addition, La Laguna is continually enhancing the accessibility of its leisure facilities. In the coastal areas of Bahamar and Punta del Hidalgo, for example, the natural pools have dedicated parking spaces, ramps, convenient walkways, toilets, showers and changing rooms. Ramps leading gently into the pools, amphibious chairs and a lifeguard service ensure that people with disabilities can enjoy a comfortable stay.

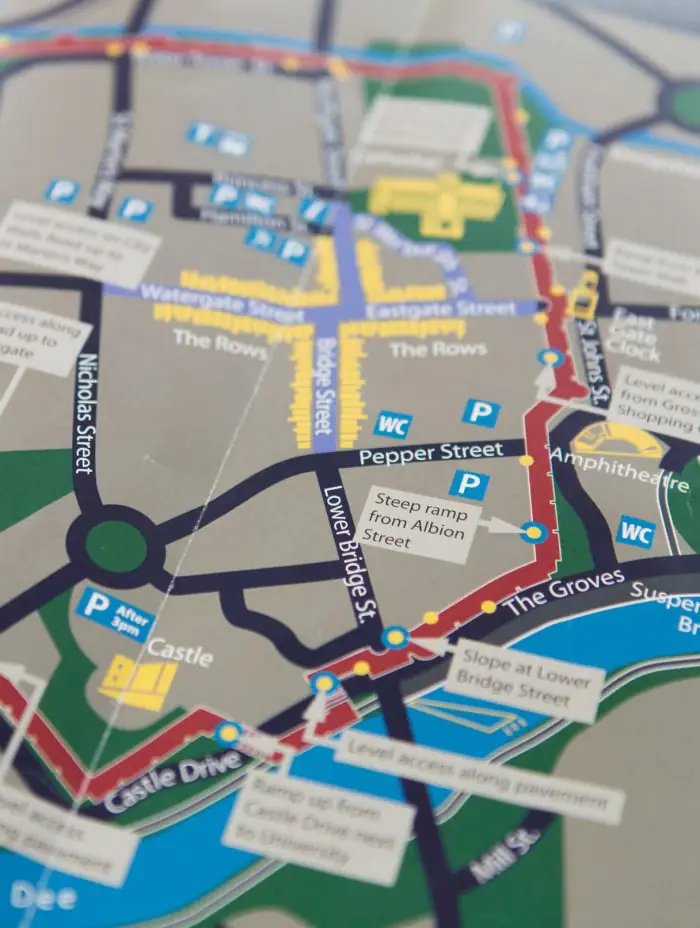

Another notable example is Chester in the United Kingdom, winner of the 2017 award. The city is renowned for its ancient walls and half-timbered houses, many of which house shops on the ground floor. To enable everyone to explore the city centre and learn about its history, 129 accessible buses were added to the fleet and 11 ramps and special toilets for people with reduced mobility were installed on the streets. All taxis in the city are also required to have sufficient space for wheelchairs. They must also have induction loops and handrails in contrasting colours.

The small Swedish town of Jönköping, once known for its match production, is now famous for something else. It is one of the most accessible cities in Europe for people with disabilities — winner of the Access City Award 2021. Working closely with organisations that support people with disabilities, the city authorities have implemented a number of initiatives aimed at making buildings, products and the environment accessible to as many people as possible.

Improvements throughout the city include tactile maps and signs, audio descriptions, tactile paving, distinguishable objects and accessible pavements, as well as barrier-free access for wheelchairs. Almost all public buildings, infrastructure, shops and attractions now meet the long list of accessibility criteria, from concert halls to one of the world’s three match museums.

Latvian cases

In 2017, Jurmala also won the Access City Award, coming in third place for its accessible seaside, convenient changing rooms, and special educational programmes for older people.

However, as stated by the Apeirons disability association in 2023, Latvia generally lacks experts in environmental accessibility, and architects are often unaware of all the aspects involved in making a building accessible to everyone. Riga Technical University believes that the key to an inclusive society is universal design, which future architects study from their first year of study.

Problematic cases

Although Sweden was one of the first countries to introduce transport accessibility legislation in 1979, research shows that serious problems remained until recently. In 2015, around 74% of buses nationwide were accessible to people with reduced mobility, but there was significant variation between counties: in some, the figure was as low as 19%. Consequently, people with limited mobility take significantly fewer trips — the study found that people with disabilities took an average of 0.9 trips per day, compared to 1.6 for the rest of the population.

Another study on urban mobility, “Cultural accessible pedestrian ways: The Case of Faro Historic Centre”, reveals that Faro’s historic centre does not meet national accessibility requirements, with ramps, narrow pavements, and other obstacles making it challenging for wheelchair users to navigate.

Venice is one of the most challenging cities to adapt. It is extremely difficult to preserve the city’s historical context while ensuring accessibility. Ancient bridges with stairs, narrow streets and cobbled surfaces all present insurmountable barriers for citizens and tourists with limited mobility. Although travel agencies and information centres provide information on accessible routes, the environment remains extremely inconvenient for these people — to reach a particular attraction, they have to make a long detour or give up on visiting it altogether.

Conclusions: what can and should be done

- The environment for people with disabilities should be designed comprehensively. Rather than considering separate ramps and handrails, it should be thought of as a large system. Sometimes, however, city authorities or building owners focus on a single aspect, such as a step-free entrance or handrails, without considering the wider route between home, the street, transport and the building.

- The issue of historic centres is particularly sensitive: preserving heritage is often considered more important than adapting buildings to meet the needs of people with disabilities, which can lead to compromises being made or the needs of these people being ignored.

- The audit of the existing environment must be transparent and not only based on formal standards, but also on how many people actually use the space. Ideally, people with disabilities should be directly involved in the project from the outset, ensuring that the process of creating the space is inclusive as well as the space itself.