adobestock.com

Brief History of Cemeteries

Since Neolithic times in Europe, Asia and Africa, that is, from about 9500 BC, the bodies of dead people were buried in caves or enclosed in rocks on the outskirts of cities or outside them—sometimes burials formed entire necropolises, that is, large cemeteries with underground galleries and crypts.

The inclusion of cemeteries in urban space is directly related to the spread of Christianity. This is a crucial moment in the development of the medieval city: it is also how it broke ties with the ancient tradition. Beginning in the 10th century, people in Europe began to be buried near or within churches to express the idea of spiritual continuity between those who died and those who remained on earth. In medieval cities, churches—and with them the adjacent cemeteries—were often the central points of the urban fabric: places for sermons and services, regular local community meetings, fairs and festivals, parliamentary meetings, trials and even executions.

adobestock.com

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the population of cities began to grow rapidly: manufactories and then factories began to appear in them, and workers regularly came to the cities from the countryside. In the course of this industrialization, not only the number of the living but also the number of the dead in the cities grew: old cemeteries could no longer accommodate all the dead. Sometimes overcrowding caused infections to enter the drinking water, and epidemics, including outbreaks of plague, broke out in some cities.

From the late 18th century, burial grounds, as spaces that could cause disease and become sources of epidemics, began to be scrutinized and reconsidered. The approach to their location in cities was also changing: for example, to solve the problem of overcrowded cemeteries in Paris, in the early 19th century Napoleon Bonaparte ordered the construction of new cemeteries in the vicinity of the city. Subsequently, the most famous among them was the Père-Lachaise cemetery, which was the first case of purposeful planning and landscaping of a cemetery.

adobestock.com

adobestock.com

At first, such cemeteries located outside the city were very unpopular. To attract customers, in 1817 the remains of the playwright Molière (died in 1673) and the writer La Fontaine (died in 1695) were reburied at Père-Lachaise, followed by the remains of the philosopher and theologian Pierre Abelard (died in 1142) and his lover Heloise (died in 1164). Thus in the nineteenth century there was a great migration of cemeteries to the outskirts of cities.

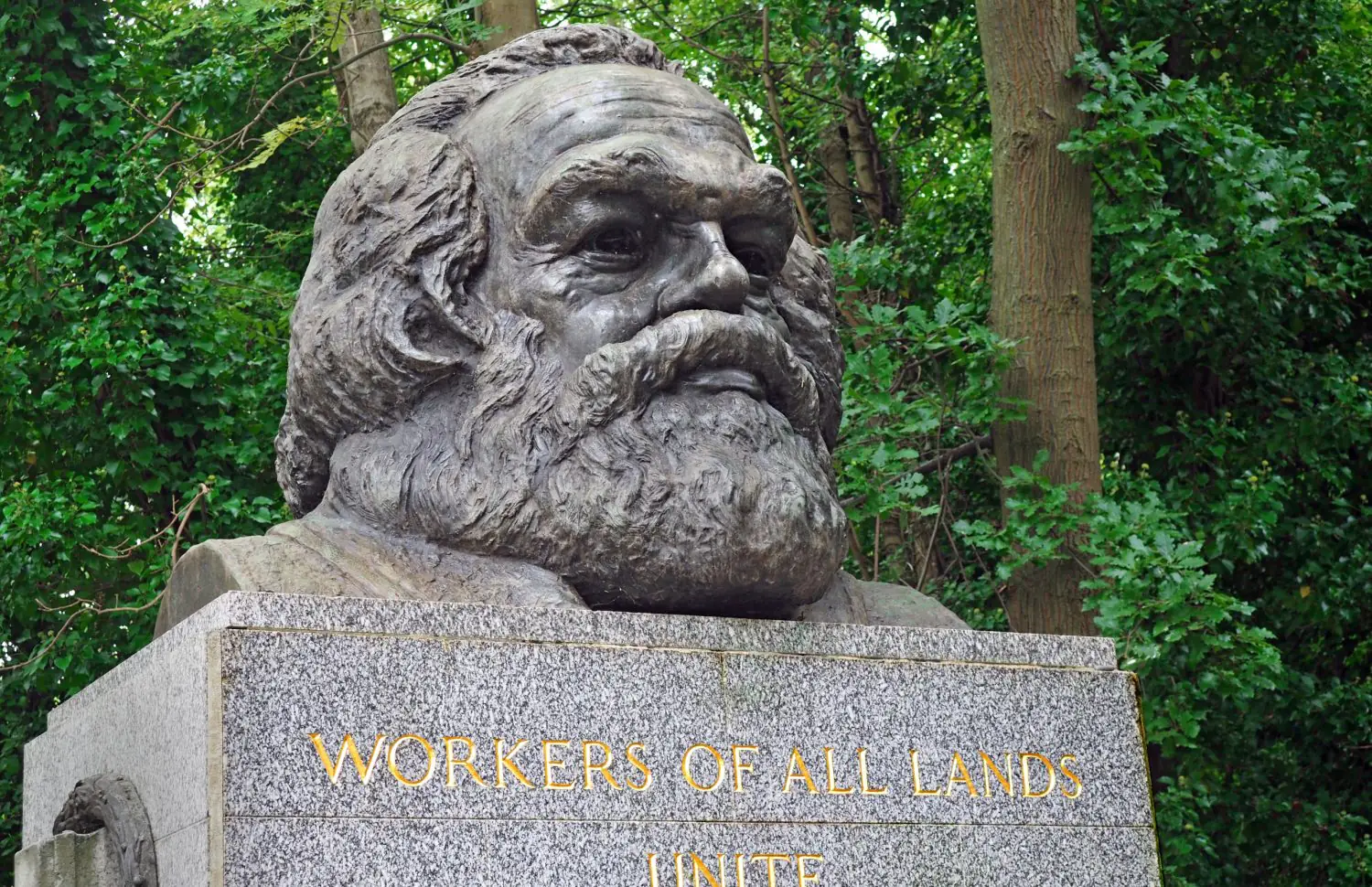

After Paris, the tradition of placing cemeteries in the suburbs spread to England and the USA: around London there appeared the “Magnificent Seven” cemeteries, the most famous of which, Highgate Cemetery, opened in 1839 under the leadership of architect and entrepreneur Stephen Geary, the founder of the London Funeral Company. In the United States in the 19th century, the tradition of “breaking bread” with the living and the dead in cemeteries gradually developed: a culture of picnics in cemeteries emerged, which existed until the 1920s.

There were not many urban parks in developing megacities, and cemeteries, which were part of the suburban infrastructure, gradually turned into a kind of urban gardens: they were used for walks and picnics, to visit the graves of famous people (these practices still exist today), and sometimes for hunting trips and carriage races. Some cemeteries even had maps and guides, and instructions for visitors on how to behave.

adobestock.com

Cemeteries as a Cultural Phenomenon

French philosopher Michel Foucault explored the phenomenon of the cemetery in his works in the 20th century: reflecting on different types of urban spaces, he introduced the concept of “heterotopia”. This word comes from the combination of two Greek roots: “heteros” (ἕτερος — “different”, “other”) and “topos” (τόπος — “place”).

adobestock.com

adobestock.com

A heterotopia is a space within a space, real or illusory, that changes or shifts the usual human experience. In addition to cemeteries, Foucault included the fair, the garden, the reflection in a mirror, and a ship on the high seas as heterotopias.

According to Foucault, cemeteries are spaces that create a special atmosphere and break the usual course of time. Foucault argued that it was in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that the cemetery became one of the city’s fears: the public consciousness developed an “obsession with death as a disease” and a stereotype that the dead are those “who bring disease to the living, and their presence and proximity near houses, churches, almost in the middle of the street, is what propagandizes death itself”.

adobestock.com

This is why the panic over epidemics that pervaded urban life in the major cities of the 18th century necessitated sanitary policies and the relocation of cemeteries to the outskirts of the city. Foucault also argues that it was with the transfer of cemeteries to the outskirts of cities or beyond that individual coffins and single graves instead of family vaults became widespread, and cemeteries became what we know them to be today: “everyone has the right to his own little box for personal decomposition,” but this is not entirely correct: tombs and vaults appeared in new cemeteries in the nineteenth century—and still do.

Cemeteries Today: Paths to Development

adobestock.com

Cemeteries are an important element of the urban fabric. The interaction of megalopolises with their cemeteries is part of their portrait and urban policies. Many cities that emerged in the Middle Ages have old cemeteries in the center. Those cemeteries that appeared in the nineteenth century in the suburbs or on the periphery are also gradually becoming urban areas: large cities are absorbing them.

Today, perceptions of what the norm is for the use of cemeteries in the city are changing again. For example, urban populations are becoming increasingly secular and multicultural, and burial and memorialization practices are becoming more diverse and less regulated by religion.

At the same time, urbanists increasingly speak of compact cities as the most sustainable form of urban development. When cities densify—this usually happens in their central and middle parts, where industrial or port areas were located in the 19th and 20th centuries— the number of people who need, among other things, green spaces for daily walks and physical activity increases.

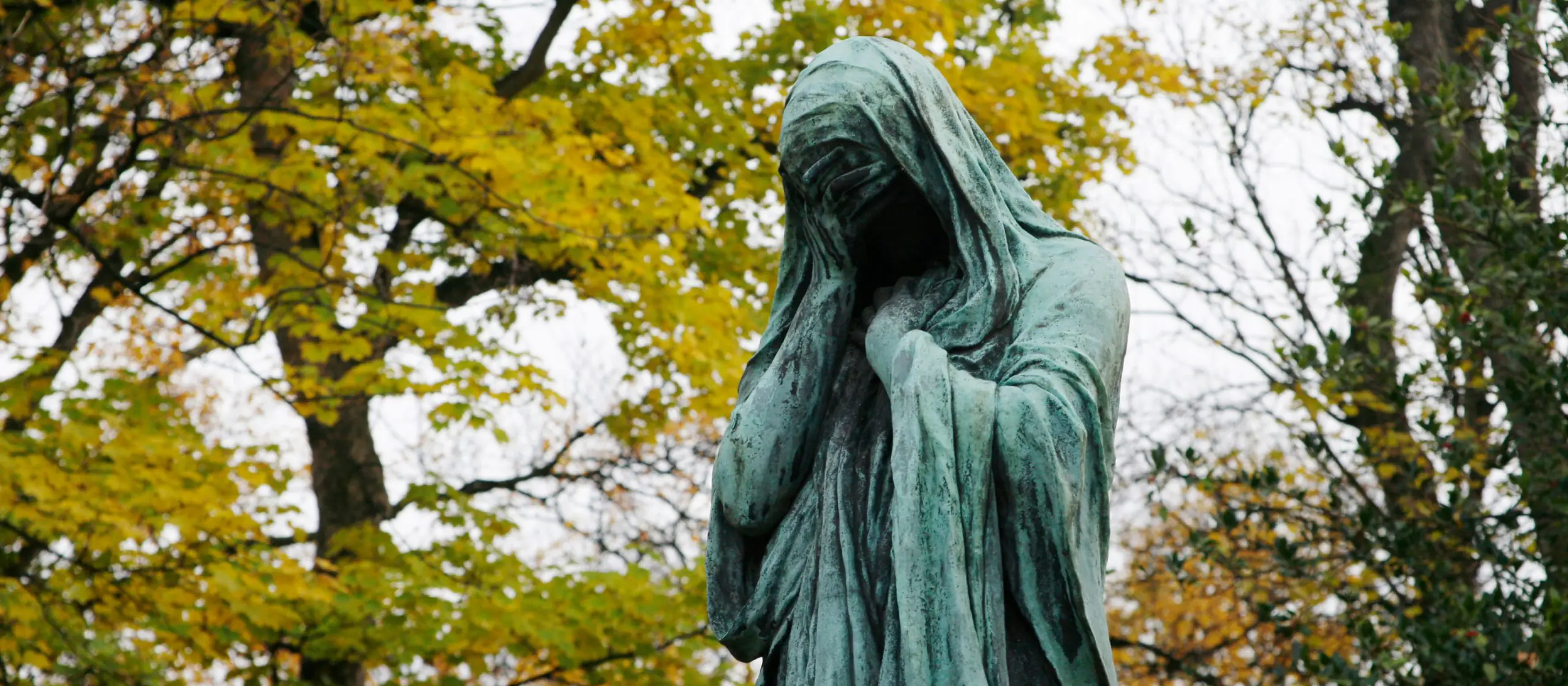

Experience from different cities shows that a cemetery can be seen not only as a closed and frightening place, but also as a public space. It can be not only a space of grief, but also an important urban point where memory, cultural heritage and the opportunity for outdoor recreation intersect.

Cemeteries in modern megacities can be used as walking green spaces: respecting the grief of those who come here to visit their loved ones, but integrating these spaces into the urban fabric rather than excluding them from the lives of citizens. This does not mean that all cemeteries should become parks with different entertainment areas: they remain special spaces that remind us of the existence of death—and allow the living to gradually process their grief at the loss of their loved ones. But if cemeteries become more open to citizens, they will also become more visible and safer, and the risk that they will one day be built up (which often happens with old cemeteries) will be significantly reduced.

A few Latvian cemeteries worth visiting have been covered by our colleagues at Neighborhood.

adobestock.com

The material was prepared with umagamma team.