Latvia first participated in the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2002. In response to the exhibition’s theme, NEXT, the Latvian Center for Contemporary Art, architect Gunārs Birkerts and the group of artists Ma1z3 presented the project “Castle of Light”.

The exposition was dedicated to Birkerts’ largest and most famous project, the Latvian National Library. At that time, it had not yet been built. According to the curators, this building, based on references to cultural and natural symbols of Latvia, embodied the national identity. It was a very important and sensitive theme in a country that had recently emerged from Soviet occupation and was aspiring to join the European Union. The scale and memorable image of the library put it among other objects of world iconic architecture flourishing at that time.

Many things had changed by 2023. Latvia is a member of the European Union. The library was under construction from 2008 to 2014 and received a lot of contradictory reviews, probably partly because after the global economic crisis, iconic projects are becoming more and more irritating. In the meantime, this year’s Latvian pavilion is much more provocative than its debut project in 2002.

facebook.com/LVpavilion

facebook.com/LVpavilion

facebook.com/LVpavilion

TCL (T/C Latvija)

The Latvian pavilion is located in the Arsenal, one of the two main venues of the Biennale (the other is the Giardini Gardens). Curator Uldis Jaunzems-Pēterson and architects Ernests Cerbulis, Ints Menģelis, Toms Kampars, and Karola Rubene transformed the 70 square meter space into a supermarket.

It looks very natural: there’s a grocery cart and basket from the real-life Rimi supermarket chain in the Baltic States. The shelves contain a lot of multicolored “goods”: cardboard items, designed with artificial intelligence. Staff members dressed as the fictional TCL (T/C Latvija) supermarket retailer are handing out booklets with the slogan “More ideas. More architecture. More products”. It looks exactly like a brightly colored promotional catalog with discount offers. The last page even has an advertisement inviting you to visit the Lithuanian Children’s Forest Pavilion.

latvianpavilion.lv

latvianpavilion.lv

Architecture as a Product

Well, but what does architecture actually matter here? The creators of the pavilion also ask this question and immediately answer it: there is more architecture here than ever before. Each product is a description of one of the 506 exhibition projects from the previous ten biennales in which Latvia took part.

latvianpavilion.lv

latvianpavilion.lv

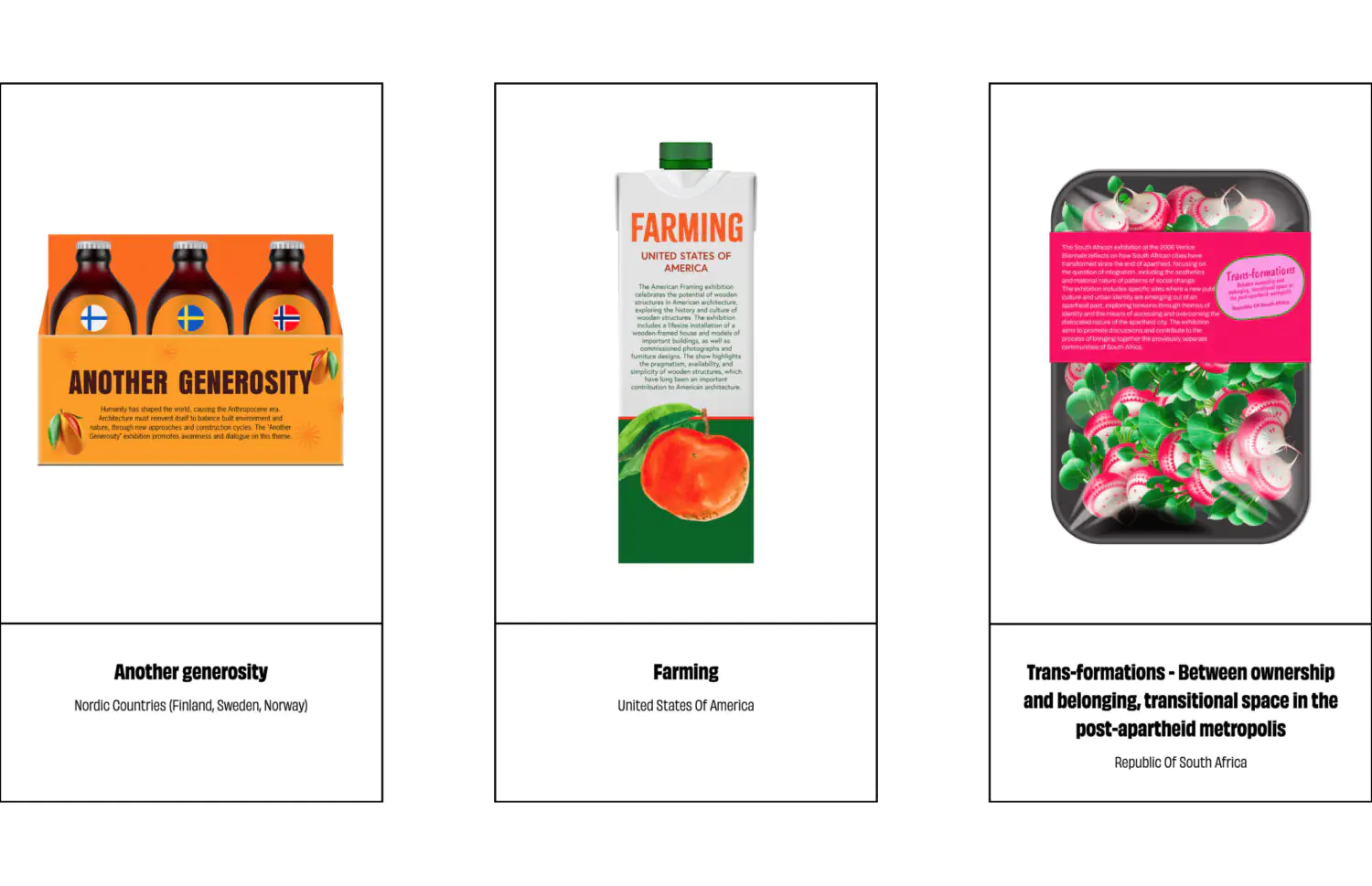

Here you can get Hotel Polonia chips – named after the Polish pavilion, which was named the best at the fair in 2008. It can be complemented with a set of beer bottles Another Generosity with three flags of the Nordic pavilion: Norway, Finland, and Sweden, or a jar of Czech UNES-CO from 2018. There are also non-alcoholic drinks from the same period: juice packs Structures of Mutual Support from the Philippines and Urban Rural Living from Uzbekistan.

Visitors are invited to choose their three favorite products, check them at the cash register, and get a special receipt. Through this game, the pavilion’s authors unveil the title theme of the current exhibition—“Laboratory of the Future”. The pavilion becomes a supermarket of ready-made ideas capable of influencing the world’s fate. The only question is how humanity will use it.

facebook.com/LVpavilion

Architecture vs Capitalism

Another dimension of the project is the place of architecture in the system of capitalist relations and its criticism in the context of the Architecture Biennale. Architecture is as much an object of consumption as a bottle of detergent or yogurt. And its over-consumption is similar to the way people, when they arrive at an exhibition, feverishly wander between the national pavilions, trying to see everything at once.

But there was more than just criticism of the architectural institution here. In a curatorial text on the pavilion’s website, Jaunzems-Petersons says that while working on the project, the team came to the conclusion: “Our view of the supermarket was too simplistic”.

The retail space is undoubtedly subject to stereotypes and is most often associated with the cult of consumption. But not everyone remembers that during the COVID-19 pandemic, supermarkets became one of the few truly safe spaces—all thanks to strict hygiene standards and ventilation and disinfection systems.

“And if our view of the supermarket is simplistic, how can we be sure that it is also not the case with architecture?”, Jaunzems-Petersons writes. Good question, definitely worth asking in the future.

One Film and Two Books to Understand the Latvian Pavilion

The authors of the pavilion developed their idea based on a broad cultural and theoretical context. Here are a few works that can help understand the meanings of this project better.

Noise: The Political Economy of Music, Jacques Attali

Magnum opus by Jacques Attali. He is a French economist, writer, former advisor to the French president, and ideologist of globalization. His work is devoted to the role of music in the political economy. Architect Marcos Novak draws on the book: in his essay “Behold! A Bold Experiment Unfolds Latent Architectures in Liquid Space!” he writes that the supermarket “facilitates a world dialogue while maintaining the uniqueness of local content”.

Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher

British philosopher Mark Fisher’s widely acclaimed work, in which he writes about depression and depoliticization in the context of neoliberalism. The historian Kiril Kobrin, in his essay “Omnitopia”, uses the most famous phrase from the book, “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism” to lead the visitor to believe that modern shopping malls are similar to paradise.

“White Noise”, Noah Baumbach (2002)

“Look how bright. Look how full of psychic data. Waves and radiation. All the letters and numbers are here, all the colors of the spectrum, all the voices and sounds, all the code words and ceremonial phrases. We just have to know how to decipher it”.

The pavilion’s architect, Ernests Сerbulis, begins the text “Supermarkets As Future Laboratories” with this quote from the film. He writes that although the stores do not have outstanding architecture, the architects here have a lot to learn: they are extremely functional spaces that are capable of operating 24/7 and yet they are open to the public. All this makes supermarkets the perfect “laboratory of the future”.