Typically, pocket parks are no more than 0.4 hectares in size. Pocket parks are also called “Parkettes”, “Mini-Parks”, “Vest-Pocket Parks” or simply “Vesty Parks”, “Green Pockets”, “Street Corner Parks”.

The concept of pocket parks does not yet have a unified definition among scholars and researchers. Public green spaces, regardless of their shape, position and boundaries, can be classified as pocket parks. The only criterion is scale: such parks should be significantly smaller than most conventional urban parks.

archdaily.com

Today, planners distinguish three types of pocket parks: active, passive and bonus parks. Active parks have a specific use scenario: they may have a playground or a mini basketball court. Passive parks are usually a few benches or tables centered around, for example, a small fountain. And bonus ones are not large green fragments at all, occupying several dozen square meters at intersections, former car parks, near shops and cafes.

Miniature urban parks emerged from the reconstruction of European cities after World War II. At that time, many large cities faced a shortage of capital, labor and materials to carry out the reconstruction of large parks. Because of this shortage, shortcuts had to be found to rebuild cities and return them to normalcy. These constraints favored the conversion of heavily damaged areas into small public parks.

Later in the 1950s, the European concept of small urban parks began to spread to the United States. While in Europe it was more of a necessity, in America this planning technique was used as a way to manage urban land more efficiently, as well as to improve the quality of life of citizens and the availability of green space.

landezine-award.com

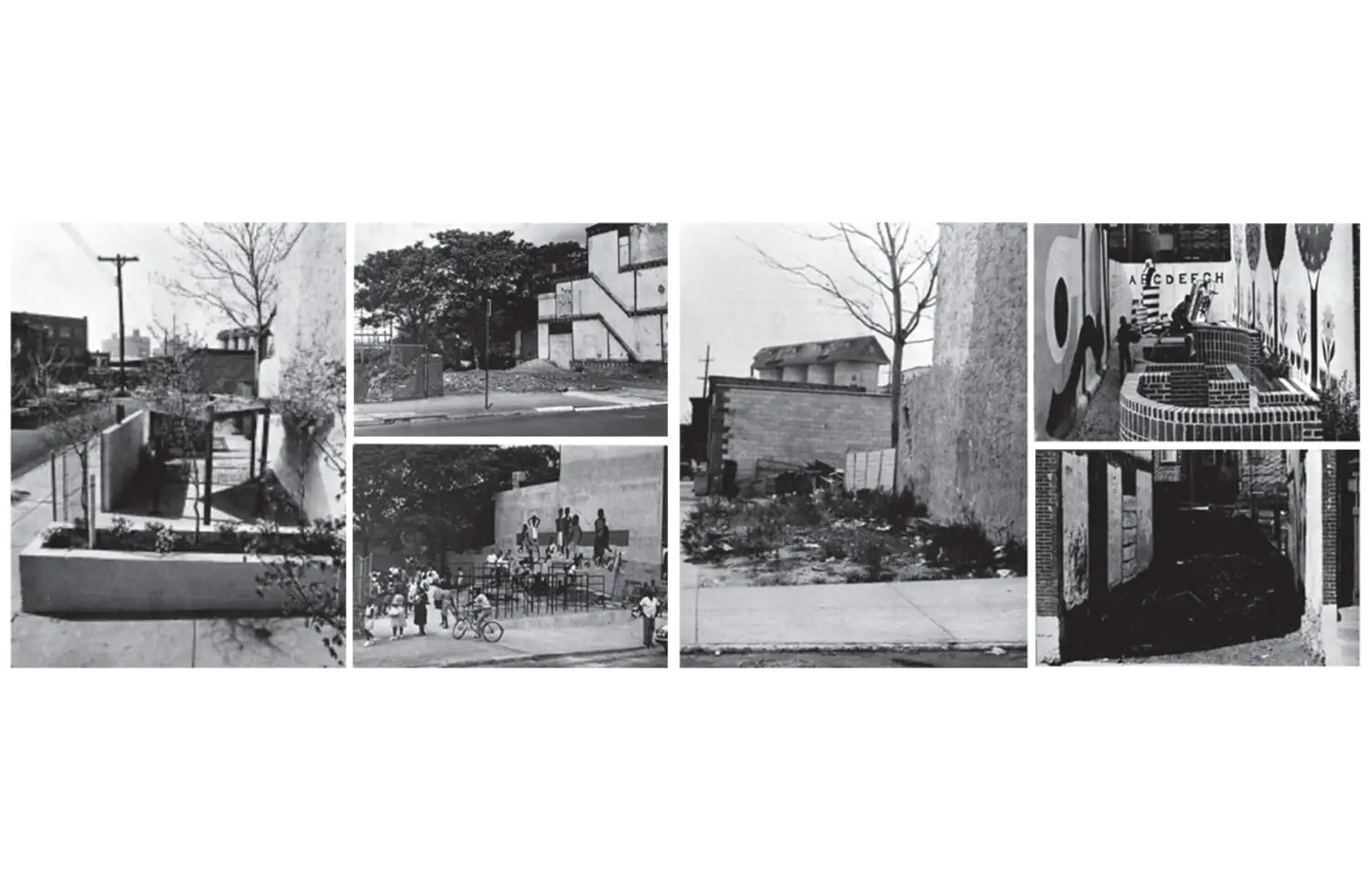

Landscape architect and professor Karl Linn played an important role in adapting European mini-parks to American cities. He convinced city officials in Baltimore, Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia to create neighborhood public spaces on unused and abandoned land.

Philadelphia was one of the first cities to create pocket parks: between 1961 and 1967 there were 60 mini-parks. They were built on vacant or abandoned lots in low-income neighbourhoods that lacked public open space. These parks involved local communities in design and construction and emphasised children’s play areas.

Photo: City of Philadelphia & Philadelphia Neighborhood Park Progam, depts.washington.edu

depts.washington.edu

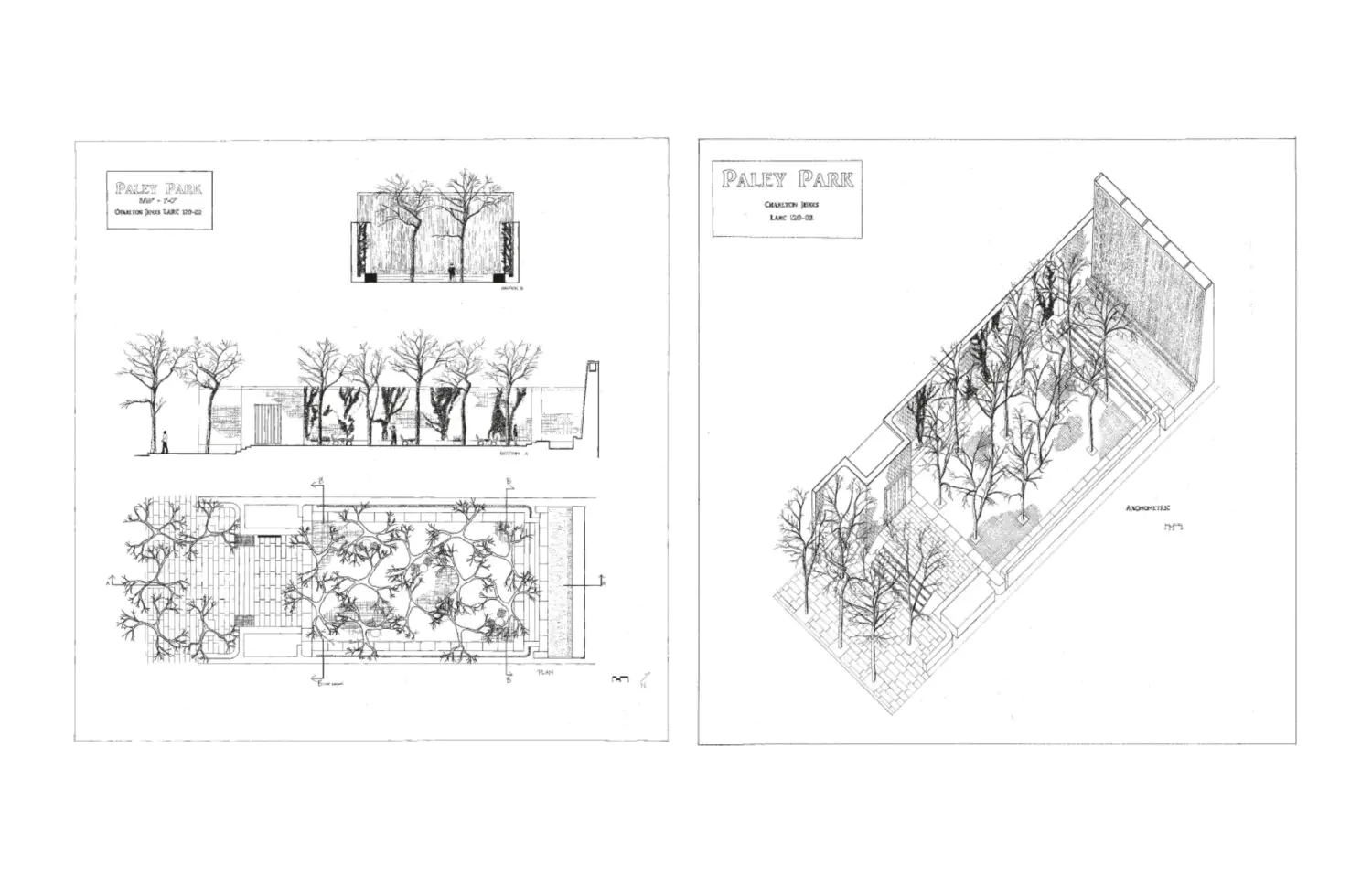

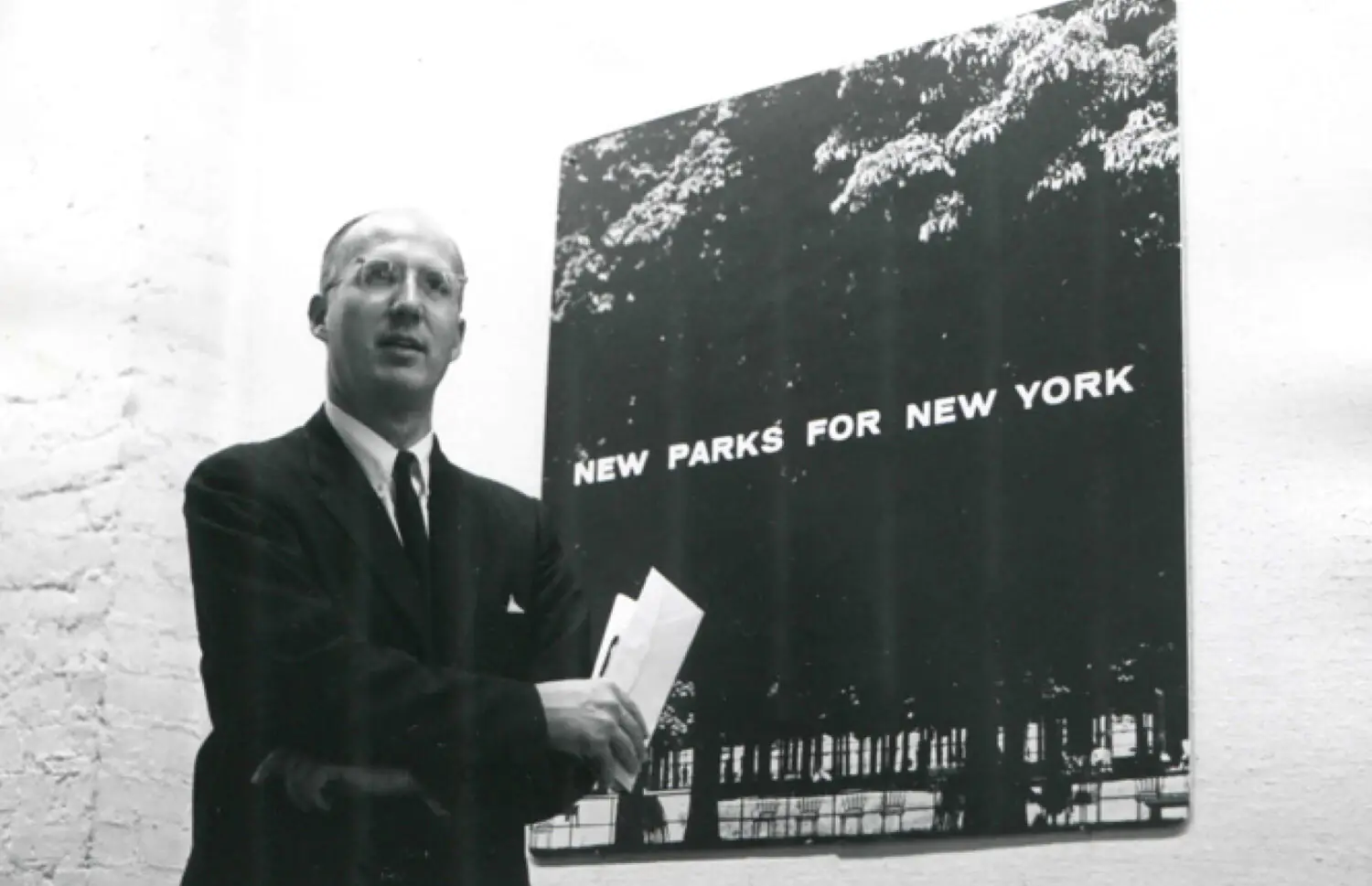

Whitney North Seymour Jr. also played an important role in popularising the idea of pocket parks. During his tenure as president of the New York City Parks Association in 1963, he spoke of parks not just as amenities but as necessities that “should always be at hand” and advocated the creation of pocket parks in New York City. In 1965, House of Representatives member John Lindsay endorsed the idea during his campaign to run for mayor of New York City. As early as 1965, 18 such parks appeared in New York City, and a network of 200 small recreation areas was planned. And in 1967 in Midtown Manhattan opened Paley Park (A Midtown Pocket Park: Paley Park), designed by Zion Breen Richardson Associates. It remains one of the most famous pocket parks in the world today.

www.watercubedesign.it

land8.com

Thus, the concept of “pocket park” appeared in the public and political discourse of the United States in the early 1960s. However, it was conceptualised in 1969. Whitney North Seymour, Jr. in his work “Small Urban Spaces: the Philosophy, Design, Sociology, and Politics of Vest-Pocket Parks and Other Small Urban Open Spaces” defined pocket parks as “parks smaller than most urban parks, less than half an acre in size, and often created from vacant lots, rooftops, and other forgotten and unused spaces” (1 acre is roughly 4,047 m² and half an acre is 2,023.5 m²).

creatingdigitalhistory.hosting.nyu.edu

Over the past decade, the interest of planners, managers, and consequently researchers in pocket parks has experienced a renaissance. Transformations in urban planning approaches—a focus on compactness, sustainability and walkability—climate change, and attention to the physical and mental health of city dwellers amidst epidemics have led to a growing interest in mini-parks as a planning practice.

The growing interest is also evidenced by the number of publications on pocket parks. From 1977 to 2008, it was extremely low. But from 2009 to 2019, pocket parks have increasingly attracted the interest of researchers. And the number of publications since 2020 is almost equal to the total number of publications in the previous 43 years combined. The largest number of articles were published in the USA and China (43% of the total number of publications).

The practice of pocket parks is now actively researched and applied not only in Europe and the USA, but also in Asia, especially China. In 2017, pocket parks were extensively researched here and have since been actively utilized as part of planning and design strategies. A notable example from China is the Pocket Park on Xinhua Road in Shanghai, designed by the architectural firm .SHUISHI and realised in 2020. Not a large site at all, with an area of only 106 m2, it is a 22 meter long alleyway between two buildings. The widest part of the site is less than 4.2 meters. The site used to be occupied by an illegal building, a noodle restaurant. After its demolition, the site was empty, and the city administration decided to organize a pocket park here.

archdaily.com

archdaily.com

The main eye-catching design element is the walls that frame the park: they are covered in stainless steel and reflect the light and surrounding plants: this effect creates a sense of endless green space. On one side, the mirrored surfaces are rotatable—on their reverse sides are display boards: this is how the park can be transformed into an exhibition space.

In highly urbanized areas, especially in the city center where land is very expensive, pocket parks are often the only option for creating new public spaces and green areas without major redevelopment. Unlike one large-scale park, several small pocket parks can be placed throughout a neighborhood to increase the accessibility of green spaces for citizens. Even if all available land is exhausted in an ultra-dense development, water bodies, rivers and bays within the city can be used for mini-parks.

For example, The Floating Pocket Park in the UK, designed in 2017 by the landscape bureau Garden Club London, is located by a small body of water that has not been used in any way before. This pocket park is a number of floating pontoons made of recycled plastic, with seating areas and containers of landscaping. It often becomes a venue for different events—in the summer it hosts film screenings and musical performances.

landezine-award.com

landezine-award.com

landezine-award.com

When planning pocket parks, objects that attract people’s attention are often used. This can be a sculpture, an art object, or an unusual landscape solution. For example, Tideland Studio’s New Ark Installation in the Danish city of Aarhus uses three lifebuoys made of polished steel—they lie on concrete slabs whose surface imitates ripples in the water. The reference to the image of water serves as a warning of rising sea levels, and it is also a tribute to the invisible history of the place: a hundred years ago it was flooded. Together with a terrace of pallets, plants and seating areas, the non-trivial art installation forms a small public space: a pocket park in a narrow urban alley.

Often pocket parks are created by public or private organisations, foundations, and residents’ initiative groups. For example, in the UK there is a programme to fund initiatives from local communities to create pocket parks. In this sense, mini-parks can be an effective part of placemaking toolkit.

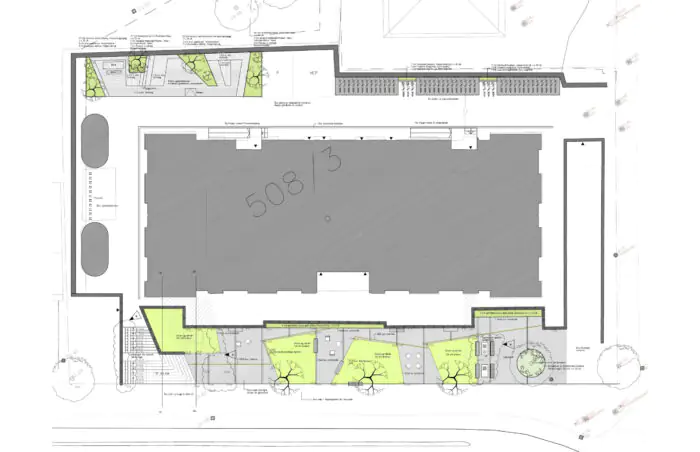

An example of participation of public non-profit organisations in the life of the city is a pocket park in Oslo, created in 2021 by the Foundation for Student Life in Oslo and Akershus (SIO, studentsamskipnaden i Oslo), designed by the landscape bureau IN SITU. It is a small public space at the student dormitory, organised after its renovation. There are benches and other seating, a car park for bicycles and scooters and green islands framed by Corten steel.

and Åsa Hjorth

www.insitu.no/pilestredet-studentboliger

and Åsa Hjorth

www.insitu.no/pilestredet-studentboliger

www.keitilige.com

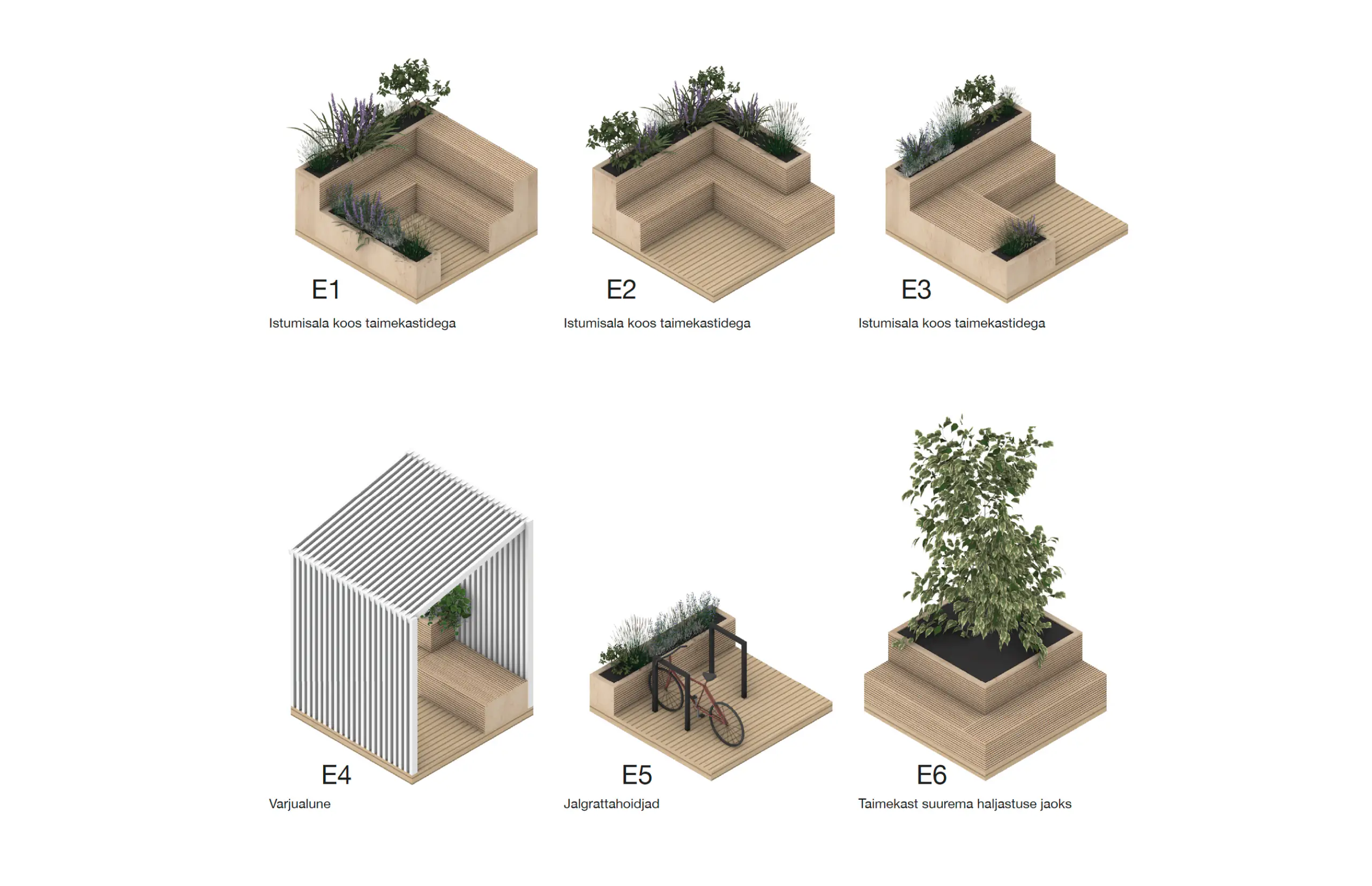

The idea of pocket parks is attracting the interest of municipalities and local communities in the Baltic States as well. Although so far these are rather tactical temporary solutions aimed at exploring this direction. For example, in 2022, the first three pocket parks appeared in Tallinn on Kotzebue, Suur-Karja and Sakala streets in the city center—car parks in front of social buildings were chosen for their location. The pocket parks are universal modules designed by Keiti Lige on behalf of the Tallinn City Council.

This is a pilot project, so the modules were only installed for the warm season. The aim of the initiative is to demonstrate how simple and quick urban interventions lead to positive changes. The municipality plans to get as much feedback as possible from local residents in order to expand the initiative beyond the city center in the future.

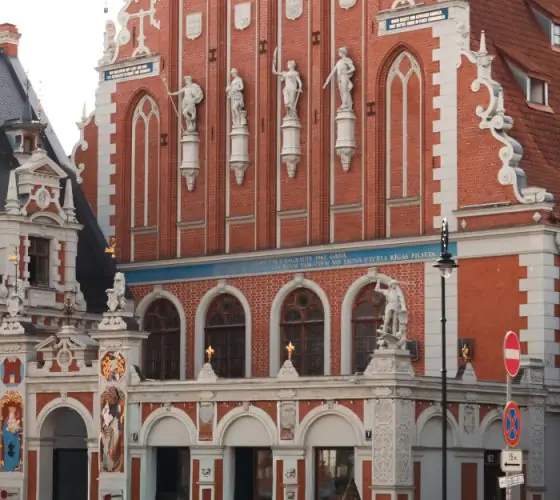

In Riga in 2021, as part of the Riga Summer 2021 cultural programme, the space Pilsētas kabata (“City Pocket”) was created at the intersection of Turgeņeva iela and Maskavas iela at the place where a wooden building stood until the 1970s. The perimeter of the pocket marked the contour of the lost house and drew attention to the voids in the fabric of the city, while offering an option to fill them.

The idea was developed by the architectural workshop T13: its founders Karlis Jaunromans and Darta Adamsonet decided to use the potential of the abandoned plot of land and, in cooperation with the NGO Free Riga and carpenter Rudolfs Janovs, turned it into an open urban space for recreation and creative activities. Pilsētas kabata offers different scenarios of space utilisation based on the principles of modularity. Since its opening, the square has hosted various cultural events: exhibitions, a chess tournament, a children’s day, a graffiti masterclass, poetry readings and a fashion tournament.

fold.lv

Mini-parks can also be integrated into the city’s transport infrastructure. An example of such integration is the renovation of the Soviet bus station in Vilkaviškis, Lithuania, designed by the Balčytis architectural bureau. During the renovation of the building, the existing triangular-shaped green area next to it was landscaped—a pocket park appeared here.

Cafes and shops and a concrete roof with outriggers link the building and the park to each other. Circular openings in the roof allowed the existing trees to be preserved. Notably, for the flower shop, a separate growing area under one of the openings in the canopy has been set aside to attract birds.

The renovated Vilkaviškis bus station was shortlisted for the European Mies van der Rohe Prize 2022. And articles in the national press led to a mini-Bilbao effect: people from all over the world started coming here to see the unique project.

Pocket Parks are now a cost-effective and efficient green solution for replenishing open spaces in densely populated urban areas. It is also an effective solution for the revitalisation of abandoned sites, which are often too small to be fully developed.

Studies show that small and medium-sized parks—attractive and well-maintained— have a positive impact on property values in neighborhoods, and can therefore contribute to the process of gentrification.

But it is important to note that pocket parks are sometimes easier to create than to maintain: they offer people a limited set of scenarios, so they require ongoing support from local communities and municipalities, regular maintenance, programming and adaptation to changing user demands.

Another our article is dedicated to Riga’s major parks and forest parks and the potential they have for development.

The material was prepared with umagamma team.