Where Did the Ornament Go?

One of the most vociferous campaigns against ornaments was launched by the Austrian architect Adolf Loos: in 1908 he published a book entitled “Ornament and Crime”, in which he eloquently condemned the use of these patterns: “The spectacular menus of past centuries, which all include decorations to make peacocks, pheasants and lobsters appear even tastier, produce the opposite effect on me. I walk through a culinary display with revulsion at the thought that I am supposed to eat these stuffed animal corpses. I prefer roast beef”.

Although Loos was against ornamentation in the most superficial sense – three-dimensional, plastic decorations for the home, furniture and household objects – his words were seriously heard and supported by many would-be modernists in Europe. Furthermore, bearing in mind that traditional ornamentation is in fact much closer to abstract than to classical art, it was to be abandoned: the modernists divorced themselves from history and “purged” everything superfluous.

Fortunately for us, the decrees of Loos and his contemporaries were not universally accepted. In the first half of the century, new nation-states, such as the three Baltics, Norway and Finland, explored their roots and folk art (including ornaments) in depth.

Ornaments in Latvia

latvians.com

latvians.com

latvians.com

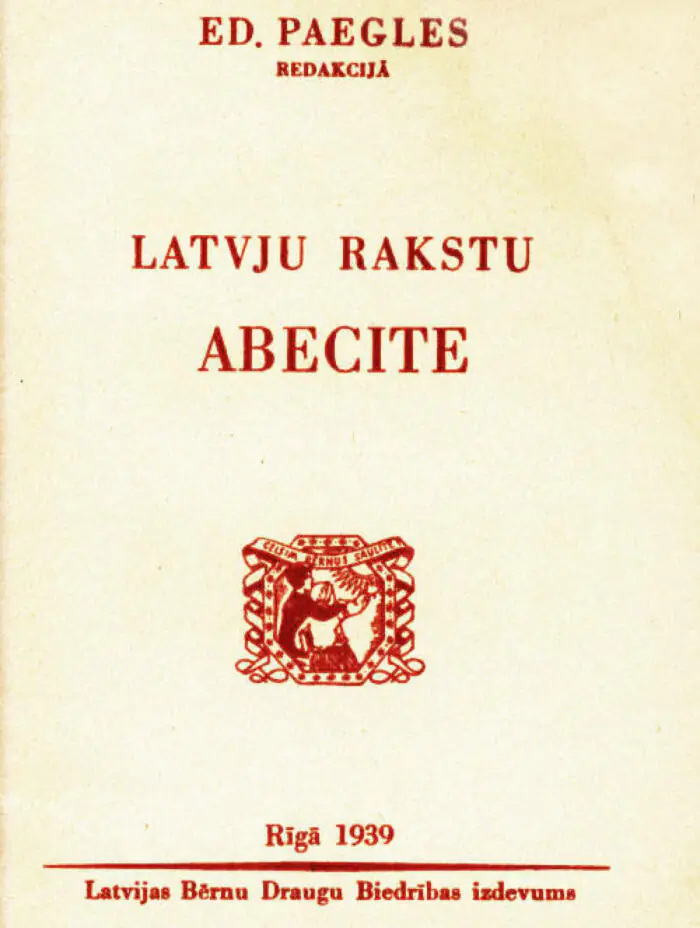

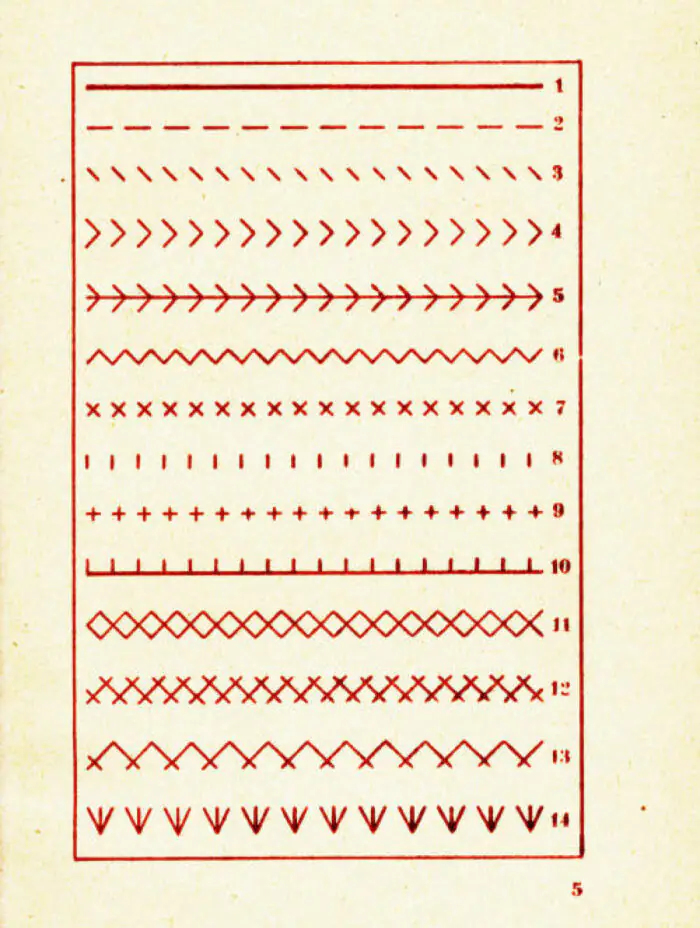

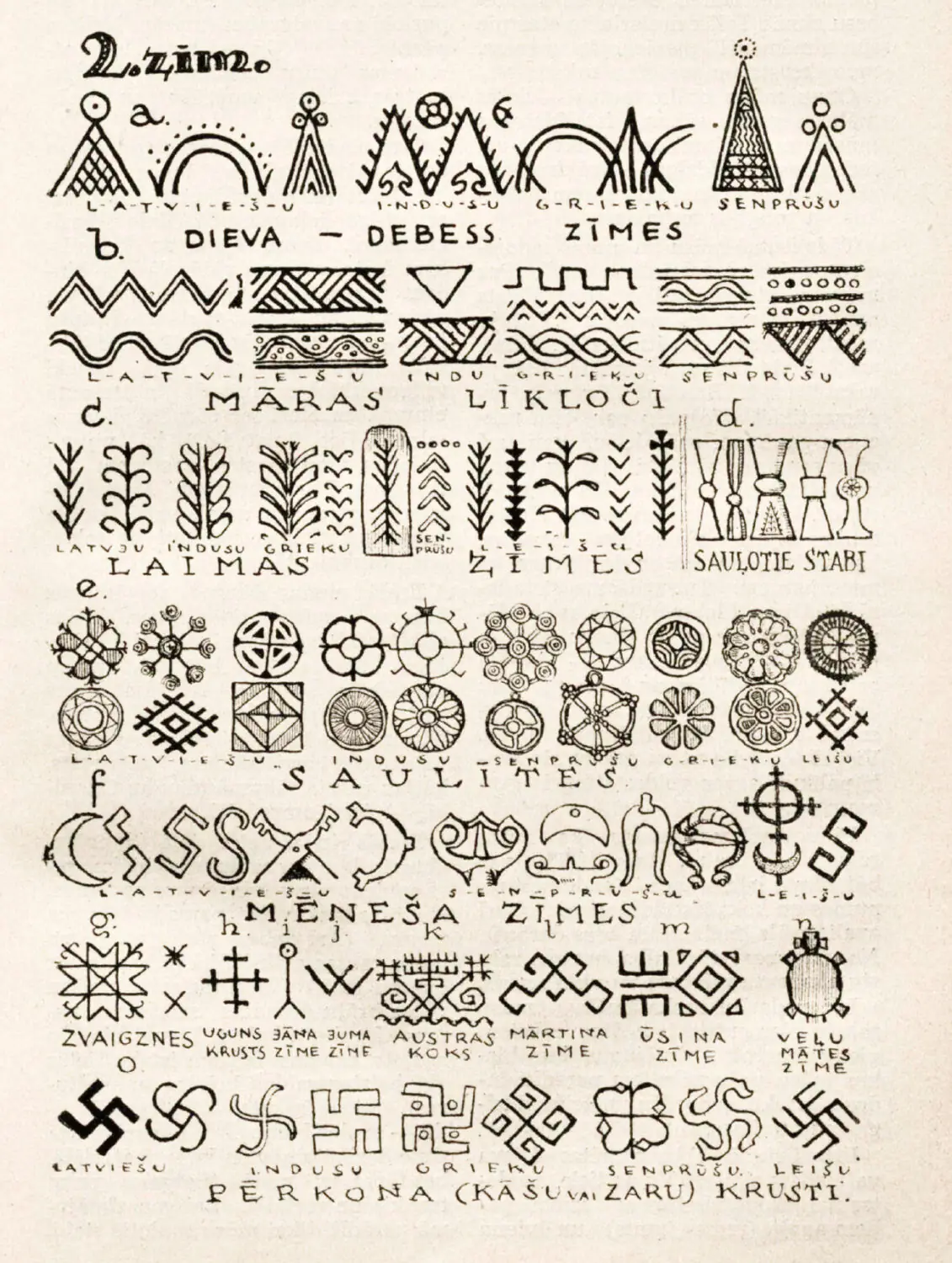

In 1940, ethnographer and populariser of Latvian applied arts Edvards Paegle published “A Collection of Latvian Folk Patterns”. In this book, he studied the origins and forms of Latvian ornaments. Paegle stressed that Latvian ornaments have preserved their ancient, abstract form.

This distinguished them from ones of neighbouring regions: the Estonians, Lithuanians and Slavs transformed simple geometric signs into fantastic animals and exotic flowers, while the Latvians moved away from “animalistic and vegetative motifs” and turned them into abstract linear figures.

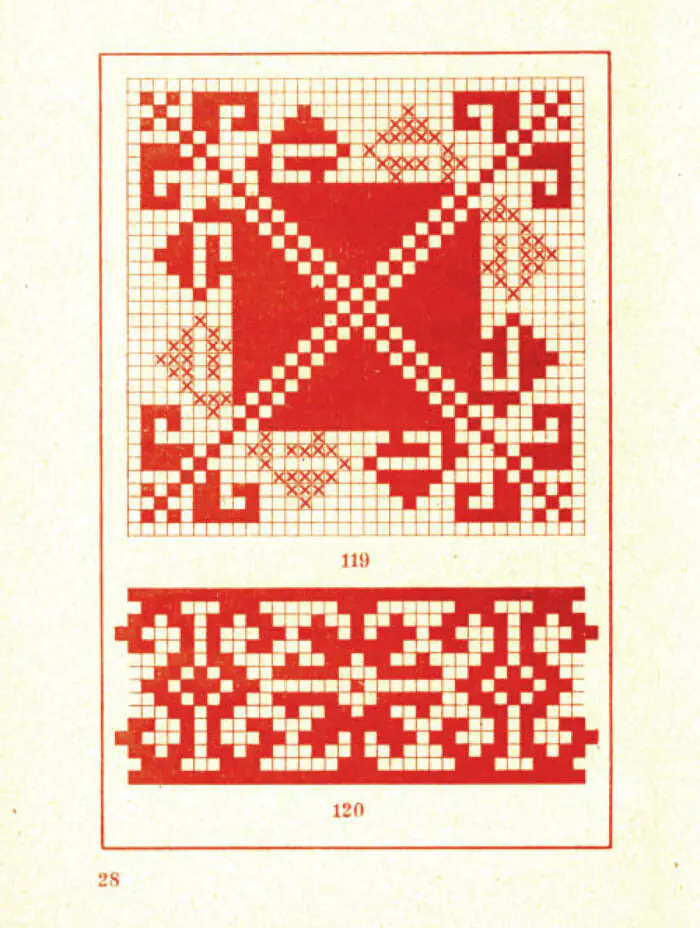

lfk.lv

From this “aggregation of atoms” thousands of Latvian ornaments are formed. There are approximately 5 500 glove patterns in the country alone, none of them alike. Each of the 553 municipalities has its own tradition of folk costumes and ornamentation. From them you can identify the town, village and sometimes even the particular farm from which the item originated – from any pattern you can infer the history of a particular family and region. This form of art has survived in Latvia and is still actively used in the manufacture of jewellery and household objects.

Researchers identify between 10 and 20 main ornaments. One of the most popular classifications was developed by Jēkabs Bīne, a contemporary of Paegle in the field of ornamentation. Let’s take a closer look.

Sign of God

(Dieva zīme)

What it Looks Like: an upward-facing triangle.

What it Means: a sign of heaven and The Sky Father (the oldest Latvian deity); associated with masculine power and the ‘roof of heaven’. It was placed on rooftops so the inhabitants could live ‘under’ God. Often depicted in combination with a circle at the top as the eye of god.

The Māra Zigzag

(Māras līklocis)

What it Looks Like: zigzags and intersecting horizontal lines.

What it Means: Māra is the goddess of motherhood, ruler of the earthly and underworldly realms. The Zigzag of Māra symbolises water, the sea and the goddess herself, who is sometimes referred to as the Black Serpent.

Signs of Laima

(Laimas zīmes)

What it Looks Like: a single or double “Christmas tree”, resembling a leafy branch or a feather.

What it Means: The sign of Laima, the guardian of souls, determines one’s destiny and the path of their life. Her main accessory is a broom, which she steams with a newborn baby in a hot bath. She removes all things unpleasant and unseemly from the home, including negative emotions like envy and resentment.

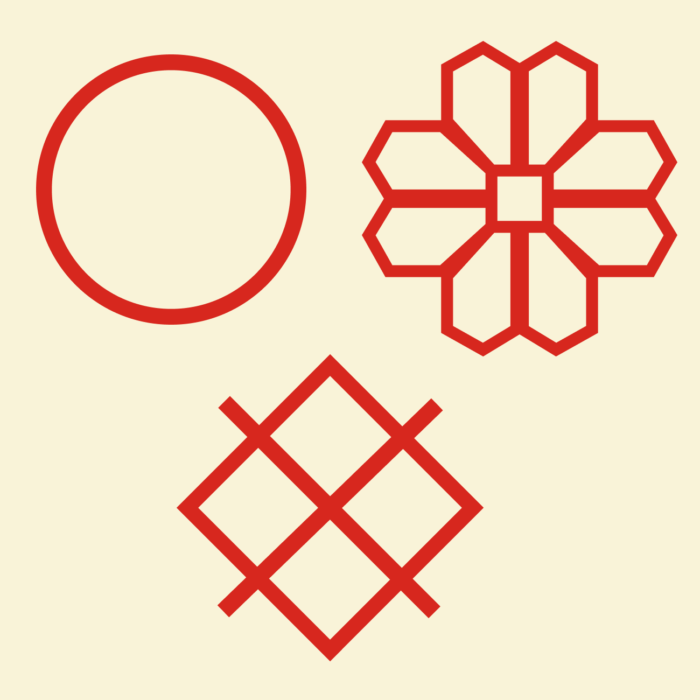

The Sun Sign

(Saules zīme)

What it Looks Like: circle, square grid or eight-petalled flower.

What it Means: the Sun represents the movement of life and motherly energy – used in women’s jewellery and clothing, as well as on spindles and other dowry tools.

The Moon

(Mēneša zīmes)

What it Looks Like: most often represented by semi-circular or open diamond shapes.

What it Means: the Moon is closely associated with agriculture – farmers were well aware of the effect the great illuminator of the night had on crop growth, so they honoured it in hopes of an abundant harvest. The moon also protected warriors, so it was attached to men’s clothing and armour as an amulet.

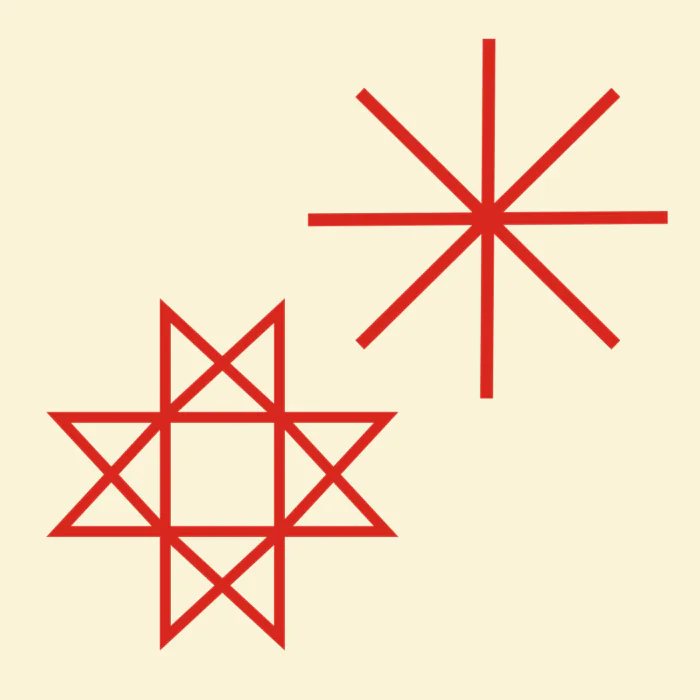

Stars

(Zvaigznes)

What it Looks Like: a cross of four, six or eight points.

What it Means: a sign of safety against the forces of darkness and the underworld. A blanket embroidered with these stars protects the soul of the one who sleeps beneath it. It is more common amongst the Finno-Ugric peoples, and is therefore more common in Latvia in historically Livonian settlements.

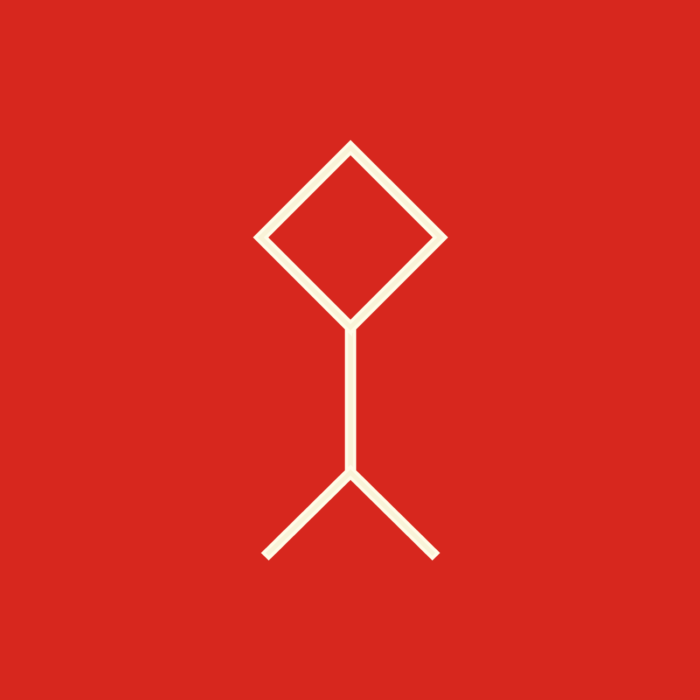

The Sign of Jānis

(Jāņa Zīme)

What it Looks Like: a triangle with a diamond connected at the apex.

What it Means: sign of masculine strength, activity and virility. Another interpretation of the symbol: the Sun standing atop of the Hill of Peace.

Jumis

(Jumis)

What it Looks Like: two crossed ears of wheat resembling an upside down “W”.

What it Means: Jumis is the god of the harvest; his sign was often used in rituals to encourage the growth of crops and was placed on roofs to ensure prosperity and wealth for the family.

The Austra Tree

(Austras koks)

What it Looks Like: a schematic “tree” with symmetrical branches.

What it Means: a model of human knowledge and perceptions of the past, present and future, symbolising the flow of life. In Latvian tradition it is used as a feminine symbol – on wreaths, woollen fabrics, shirts and jewellery alike.

The Sign of Mārtiņš

(Mārtiņa zīme)

What it Looks Like: a representative image of two crossed roosters.

What it Means: the rooster is a symbol of dawn, awakening and alertness, as well as masculinity. For Latvians, as for Slavs, it was the spirit of the master of the house, so when settling in a new home, a rooster was let in first and left overnight. The bird’s song at dawn was a good omen.

Usins

(Usiņš)

What it Looks Like: an abstract image of two horses and a chariot of fire.

What it Means: Ūsiņš is the spirit of heavenly horses and light, associated with spring, the beginning of farm work and the care of horses. He was worshipped for good harvests and this sign brings good luck for travellers.

Mother of Spirits

(Veļu māte zime)

What it Looks Like: a representation of a frog.

What it Means: symbol of the afterlife and the night, as frogs are most active in the dark; the Spirit Mother sign protects the souls of the dead and keeps them connected to the realm of the living, which is why it is particularly popular on gravestones in Kurzeme.

Thundercross

(Pērkona krusti)

What it Looks Like: a swastika, often in more complex forms.

What it Means: symbol of luck, energy, thunder and wind. The sign of the thunder god was carved on cribs and woven into the belts of newborns as protection against evil gazes. One of the oldest symbols not only in Latvia, but also globally, it is roughly 5000 years old and was first seen in the Baltic States between the third and fourth centuries.

Other Popular Ornaments

The Sign of Māra

(Māras zīme)

What it Looks Like: a downward facing triangle.

What it Means: Māra is the motherly goddess; ruler of the earth and the underworld. She symbolises the material world and strength, the opposite of the Triangle of God. Intertwined, these two signs form the hexagonal cross of the Morning Star (Auseklis), a symbol of balance and harmony.

The Cross of Māra

(Māras krusts)

What it Looks Like: a cross with perpendicular lines at each end.

What it Means: a symbol of the earth and femininity. Associated with the household, fire and fertility. The crossed ends symbolise both life and death.

Auseklis (Morning Star)

(Auseklis)

What it Looks Like: a star made up of eight lines.

What it Means: represents the triumph of light over darkness. In folklore, Auseklis is portrayed as the son of God, with the Sun’s daughter as his wife. Traditionally, an Auseklis is drawn without removing one’s hand from the surface with just a single line. This is usually done during the Summer Solstice and on Christmas Eve.