stock.adobe.com

Tallinn and Riga, two Baltic capitals with a unique cultural and architectural heritage, could be seen as sister cities in many ways. Both cities have witnessed a turbulent history that has shaped their urban landscapes. Both are rich in industrial architectural heritage, and there is a growing need to redefine it.

In Tallinn, however, numerous examples of innovative and creative adaptive reuse projects have given a new life to historic buildings and enriched the urban fabric. These industrial aesthetics evoke a strong emotional response from residents who are attracted by the synthesis of familiar historic architecture and modern design techniques.

Let us take a closer look at some of Tallinn’s industrial architecture renovation projects: they showcase the city’s architectural prowess and can serve as inspiration for other cities, including Riga.

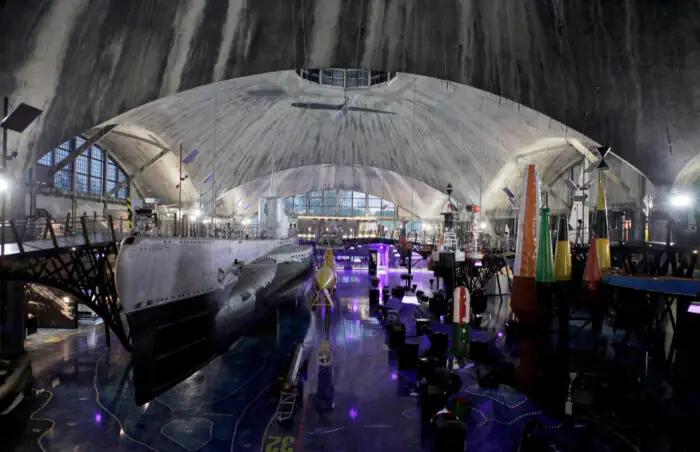

Seaplane Harbour Museum

The former seaplane hangars house a new part of the Estonian Maritime Museum: the Seaplane Harbour. Designed in 1916, the Harbour stood as the world’s pioneering long-span reinforced concrete structure of its size (36.4 by 116 metres), a true marvel of engineering. KOKO Architects undertook the meticulous restoration of the deteriorating hangars in 2012, skillfully enhancing their distinct geometry with subtle additions, like the very multilevel exhibition crossing the entire space and the glass façades.

archdaily.com

archdaily.com

Within the expansive hangar space, the museum is divided into functional units both vertically and horizontally, creating an immersive exhibition experience across three levels. To establish a visual connection between the museum and the city, two of the original concrete walls were replaced with transparent glass panels, allowing for the integration of public events.

The interior of the museum is complemented by contemporary furniture and sleek metal elements, blending with the industrial ambiance of the hangars. The architects’ work with lighting design deserves a special mention: at times cosmic, at times theatrical, the museum’s light instantly rejuvenates the space.

The museum has already received public acclaim and has won many awards, including European Heritage Award.

Kai Art Centre

Noblessner is a historic district in Tallinn, located on the shores of the Baltic Sea. In 1912, a shipyard was laid out that once produced ships for the Russian Imperial Navy, housing a secret submarine factory among other facilities. Today, Noblessner has become one of Tallinn’s main cultural hubs: the district is rapidly developing, cleverly incorporating modern cultural facilities into the historical architecture of the industrial era. At the heart of Noblessner, the multifunctional Kai Cultural Centre opened in 2019, located in the very premises of what once was a secret submarine factory.

instagram.com/kaicenter

instagram.com/kaicenter

The first floor of the Kai Art Centre unveils an expansive exhibition space, while the ground floor houses food studios and restaurants. Neutral white walls draw attention to the characteristic curved roof with a skylight in the centre. The architects deftly juxtapose elements of the industrial heritage with minimalist furniture. Remarkably, certain parts of the centre proudly preserve the rough industrial texture on their plastered walls—a small testament to the meticulous restoration approach undertaken by the architects.

Äripäev Office

A former plywood factory in a historic part of Tallinn, dating back to the early 20th century, went through a series of renovations before undergoing final transformations in 2014. Arhitekt 11 took on the task of preserving the building’s industrial feel while adapting it to the contemporary needs of a leading business news publication in Estonia.

The inherent spaciousness and lofty ceilings that are a common feature of many former factories proved to be an ideal canvas for an open-space office conversion. Workplaces are located around the inner perimeter, and in the centre there are meeting rooms, a library and a café. The architects retained original elements of the factory, such as the limestone walls and concrete beams. They also renovated and partially opened the glass roof, inviting natural light into the office space. For those particularly interested in the industrial heritage, a small atrium has been installed between the first and first floors, where the entire post structure can be seen from top to bottom.

Furnishing the space, the architects used plywood: an elegant gesture that reminds us of the building’s past life.

Rotermann’s Old and New Flour Storage

Once an industrial area, the Rotterman Quarter is now the gateway to Tallinn’s old town for many visitors coming from the ferry terminals, currently in the midst of an active renovation and modernisation process. It combines the carefully restored and readapted original buildings with new design projects. The Old and New Flour Storage project is a synthesis of these two approaches, designed to be a focal point of the district.

archdaily.com

archdaily.com

Comprising three distinct components, this project encompasses the Old Flour Storage Facility, built in 1904 and augmented with two new additional storeys, the contemporary New Flour Storage Facility adjoining it, and a glass Atrium that connects the two structures. The ground floor hosts shops, while the upper levels accommodate office spaces.

The two extra floors added to the Old Flour Storage Facility pay homage to its original proportions, but in a different material: Corten steel. This velvety-red rusted steel complements the existing materials found in the Old Flour Storage House, such as limestone walls, brick lintels and weathered metal accents. The choice of Corten steel extends to the facade of the New Flour Storage, serving as a unifying element that provides visual continuity between the old and the new. The facade of the New Flour Storage Facility mirrors the proportions of the surrounding industrial buildings, featuring windows of three sizes that offer a view of the square and towards the Old Town. The solution is simple, but conceptually convincing.

pohjalabeer.com

pohjalabeer.com

The architects preserved and sensitively restored the structure of the brick building, while also introducing several new elements, including large glass façades and metal staircases. Most of the new interior partition walls are made of lightweight concrete blocks, but the architects also used glass partitions and sliding walls. The restoration extended to the remarkable metal doors of the former industrial warehouse that were conserved.

Like its interior, the facade balances the building’s original structure with modern elements. The new brewery’s visitor balcony, for example, uses materials, cast-iron spiral staircase and sturdy metal posts that were once actually present in the former warehouse but had regrettably been lost over time.

All these details are fascinating and give the building its own unique character. An illustrative example of how industrial buildings can be transformed into modern, functional spaces while retaining their historical value and the spirit of the era.

borgfurniture.com

The examples of adaptive reuse in Tallinn’s architecture could be valuable lessons for Riga, a city that in many ways resembles its Baltic neighbour. The success of Tallinn’s adaptive reuse projects, such as Seaplane Harbour and Kai Art Center, demonstrates the rewards of revitalising industrial zones and giving new life to old buildings. These dynamic and inspiring spaces connect the past to the present and the future. We see how industrial buildings can be neatly modernised and brought back into urban life without losing their historical significance.

When it comes to architecture and investment, it’s often like a snowball effect: the more momentum you build, the bigger and faster it grows. When an interesting development appears in a previously overlooked part of the city, it inevitably generates buzz, especially if it’s not just a new building but the reestablishment of an existing one to the public consciousness. The interest and emotional response from residents can help to draw economic and social activity to the area, creating a ripple effect of revitalization. This, in turn, can lead to more investment and development, further enhancing the area’s appeal.

And the best part? This law of attraction does not apply only to the Estonian capital—by drawing inspiration from these precedents, Riga can continue to create a thriving architectural scene from its industrial architectural heritage.

Read more about what other buildings and spaces to see in Tallinn in another article.